Worms! Worms! Worms!

My scattered thoughts on Dune: Part Two, the story's view of Islam, and the modern American empire.

I saw Dune: Part Two over the weekend. It was a fun movie, probably better than the first. Dune: Part One had a lot of grimdark exposition and stern faces, with only a glimpse of action at the end. (Don’t get me wrong, it was still aesthetically awesome.) Dune: Part Two had action, a fuller range of human emotion, nuclear weapons, and WORMS! GIANT SANDWORMS! 🏜️🪱

Film director Denis Villeneuve really captured the vision of the books. The movies are big, and loud, and slow, with the kind of expansive worldbuilding that the books excelled at. In some ways, the movies improve on the books by replacing long narrative monologues with real conflicts between characters.

Villeneuve also correctly understood that Dune is not about a fun heroic victory; it is a cautionary tale about hero worship.

The lack of angry media discourse about Dune has surprised me a little. Americans love to argue about hidden political meanings in pop culture, and the Dune series is very obviously relevant: the protagonists are fanatical Middle Eastern guerrillas fighting colonial overlords over resource flows.

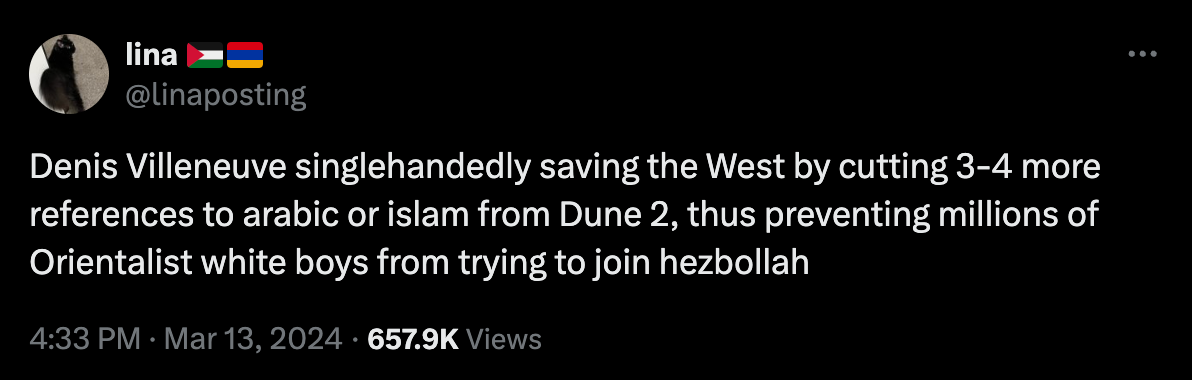

Maybe the idea is in the back of everyone’s mind, but nobody wants to bring it up, because it would require dealing with strange and complicated feelings. So instead, we’re left with Twitter memes.

The New Arab and New Lines Magazine did run articles about Dune’s “appropriation” of Muslim aesthetics in the shadow of Gaza, without addressing the content of the film. They missed the point, because Dune is a story that deeply engages with Islamic history even as it remixes it.

The Forward ran a review by Mira Fox, a journalist who was jarred by the parallels between the vicious colonial wars of Dune and the Israeli treatment of Palestinians. Fox concludes that Dune is a straightforward heroes-and-villains story, while the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is complicated.

In my view, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is less complicated than people make it out to be. And Dune is less simple than Fox seems to think.

SPOILERS TO FOLLOW:

Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel Dune is about a young prince, Paul Atreides, stranded on a desert planet, Arrakis, that is the universe’s only source of a valuable substance called “spice.” (It is produced by GIANT SANDWORMS! 🏜️🪱) Paul assimilates into the native Fremen people, learns to ride GIANT SANDWORMS, and soon becomes a Fremen prophet.

The story is meant to be ambiguous. Paul’s leadership helps the Fremen defeat a brutal empire and take control of their own destiny. But as Paul gains real prophetic powers from ingesting spice, he foresees the terrible forces that his war is fated to unleash, rippling through time and space.

The film Dune: Part Two ends with Paul’s mother Jessica saying, “The holy war begins.” It seems to be a paraphrase from the last chapter of the novel:

And Paul saw how futile were any efforts of his to change any smallest bit of this. He had thought to oppose the jihad within himself, but the jihad would be. His legions would rage out from Arrakis even without him. They needed only the legend he already had become. He had shown them the way…

Yes, the original novel by used the word jihad. The Fremen are obviously supposed to be Muslim Arabs marooned in space. They call themselves the people of Misr (Egypt) and speak Arabic throughout. One Fremen war cry is “they denied us the hajj!” Many of the other cultures in the Dune universe are also Muslim; the books refer to Ramadan fasting and “Zensunni wanderers” on distant planets.

The Arab and Islamic elements are mostly removed from the Dune movies. In one of the more egregious cases, the novel’s Paul yells “long live the martyrs” (يحيا الشهداء) in Arabic, but the film’s Paul yells alien gobbledygook that is translated as “long live the fighters.”

David Peterson, the movie’s linguist, gave a thoroughly unconvincing explanation for why the filmmakers replaced Arabic with the alien language:

Although Peterson’s version of the Fremen language retains a vaguely Arabic sound, almost all other traces of the language have been expunged from Villeneuve’s “Dune” films. Peterson claims that this is in the name of believability. “The time depth of the Dune books makes the amount of recognizable Arabic that survived completely (and I mean COMPLETELY) impossible,” he wrote on Reddit. When a user asked him to explain, he pointed to “Beowulf,” which was written around a thousand years ago and is uninterpretable to most modern English speakers. “And we’re talking about twenty thousand years?! Not a single shred of the language should be recognizable.” Key terms like shai-hulud and Lisan al-Gaib have made it into the films, but they’re treated in Peterson’s conlang as fortuitous convergences, not ancient holdovers, as if English were to one day lose the word “sandwich” only to serendipitously re-create it thousands of years later from new etymological building blocks.

The more obvious explanation is that the filmmakers didn’t want to have American audiences root for Muslim Arab guerrillas. Again, too many weird feelings for a Hollywood blockbuster. Tellingly, the filmmakers choose to keep the title mahdi for Paul’s prophethood, as well as the obscure theological term bi-la kaifa (بلا كيف), two terms that are equally as “ancient” as jihad but far less recognizable to American audiences.

And, of course, there’s Paul’s Fremen name: Muad’Dib Usul مُؤَدِّب أصول. The phrase means something like “tutor of roots” or “acculturator of roots.” For some reason, Herbert translated Muad’Dib as “desert mouse” or “the one who leads the way” and Usul as “base of the pillar,” a choice the filmmakers kept.

The Dune books have a complicated view of Islam. Herbert clearly respected Islamic civilization. Much of the plotline is inspired by Ibn Khaldun’s cycles of nomadic and settled empires. At the same time, Herbert used Islamic history as a parable for the danger of religious fanaticism, the way charismatic rebels can become brutal conquerors themselves.

He was writing in the 1960s, when Islam was still exotic to most Americans. The most recent Muslim struggles he took inspiration from, the Great Arab Revolt and the Algerian independence war, took place in faraway lands against faraway antagonists. Today, Americans are overlords in the Muslim world, and Islamist rebellions have drawn American blood.

Then again, perhaps Herbert did not intend for the evil empire to be so distant from American audience. Daniel Immerwahr, an excellent historian of U.S. empire, has pointed out that Herbert was deeply moved by his experiences with the indigenous Quileute people he grew up around.

Herbert wrote another, less famous novel called Soul Catcher about a Native American hero who befriends and ends up killing a white teenager. The protagonist resembles Herbert’s childhood Quileute mentor. (Howard Hansen, one of Herbert’s Quileute friends, was uncomfortable with the story.) Herbert, who was right wing in many other ways, seemed quite guilty about the fate of Native Americans.

The Muslim Arabs of Dune, then, were a stand-in for the noble savages that Americans would eventually regret oppressing. It is a sad twist of fate that the story stopped being a metaphor.