It's always "complicated"

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is no more or less complicated than any other ethnic war. Pretending otherwise just muddies the waters.

It’s complicated. That line often comes up in discussions of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I have a PhD in Middle East studies, and even I don’t understand the conflict. More often than not, it’s used by Israeli apologists to bash the pro-Palestine position as over-simplistic. The Atlantic is especially fond of defending Israel by appealing to complexity.

During the 2021 uprising, disgruntled reporter and Israeli army veteran Matti Friedman wrote that Americans were too quick to project their idea of racism onto Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. “The world is a kaleidoscope that can be understood only by people who are experts in each individual shard, and even then only partially,” he wrote. Cultural theorist Susie Linfield made the same argument about the “unresolved, frustratingly complex struggle” in the Holy Land. This time around, historian Simon Sebag Montefiore is arguing that the idea of Israeli colonialism “imposes a moral framework on a complex, intractable situation.”

The authors make some good, valid points. But at the end of the day, they are muddying the waters on Israel’s behalf. They believe that the metaphors Americans use to understand the conflict are unflattering to Israel, and their solution is to get people lost in the details. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not especially complex or intractable as far as ethnic wars go. In fact, it’s more straightforward than many similar conflicts.

The Ethiopian civil war is complicated. Many different ethnic groups are jostling for power within one state. Yugoslavia actually broke up into seven states, each representing a different ethnicity. The Kurdish question is also complicated; one ethnic group is living under the thumb of four different states. Kurds have different relationships to each one.

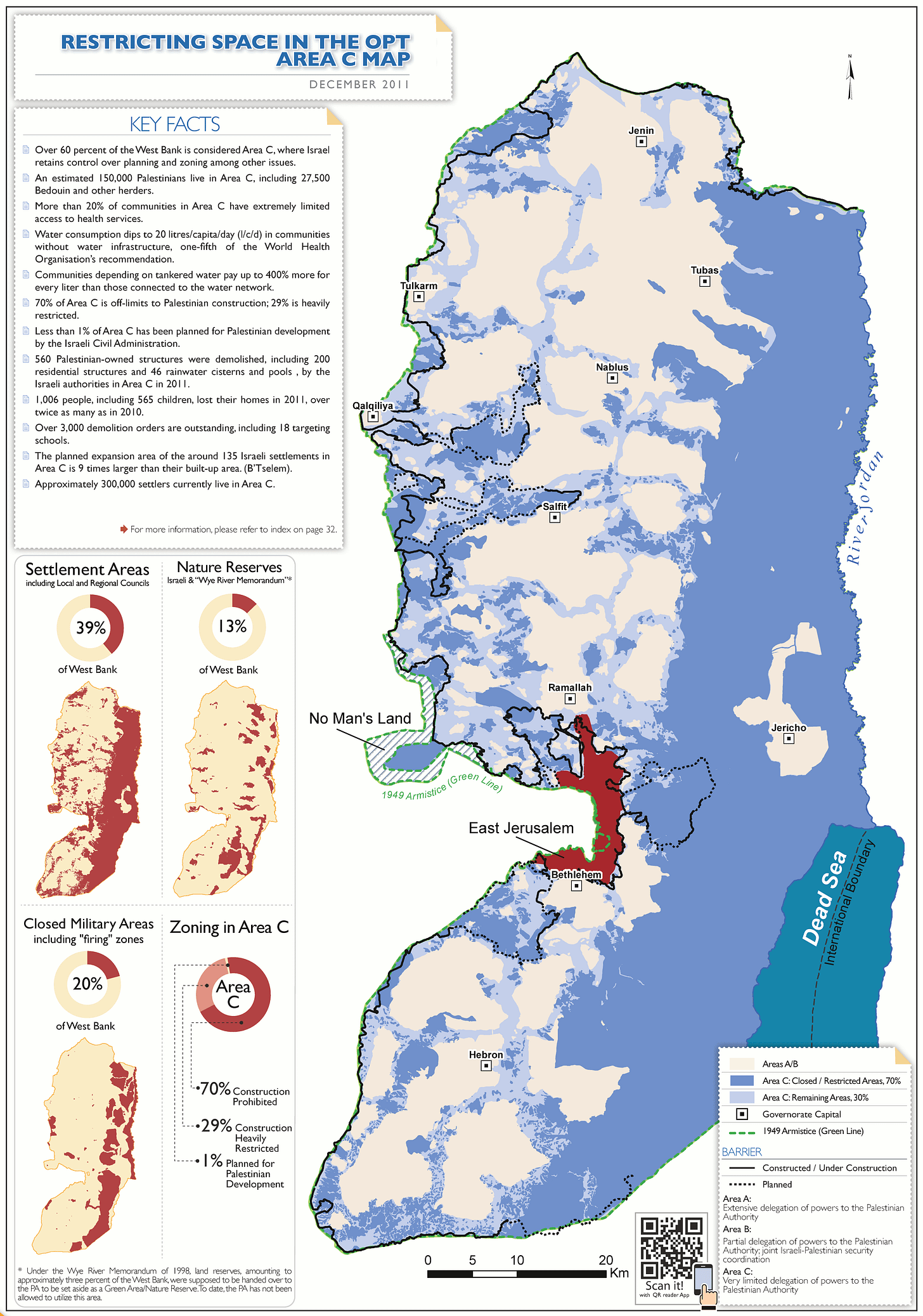

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as the name suggests, involves only two peoples. One of those peoples, the Israelis, has a state. The other one, the Palestinians, does not. The specific political arrangements on the ground are complex: Israel proper, East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza are all governed differently. The West Bank itself is split up into many different zones with a variety of overlapping power structures.

Very complicated. Then again, so was the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. For over thirty years, there was an independent Armenia, an independent Azerbaijan, and a disputed Karabakh under an unrecognized Armenian government. The history and legal status of Karabakh involved a dizzying amount of detail, before Azerbaijan reconquered it in 2023.

The big picture was fairly clear, though. Karabakh’s Armenians had fought for self-rule, under Armenia’s protection, and terrorized a large number of Azerbaijanis out of their homes in the process. Three decades later, Azerbaijan terrorized the Armenians into fleeing the entire land. Someone doesn’t need to memorize the OSCE Minsk Group countries, the Madrid Principles, or the seven disputed rayons to understand what happened.

The current war in Israel and Palestine is also an easy story to tell. Israel has tried to turn as much of the Holy Land into a Jewish homeland as possible, often by force. Palestinians have jealously guarded whatever land they can keep as a Palestinian homeland, often with violence. This month, Palestinian rebels from Gaza broke through Israeli containment and terrorized nearby Israeli villages. Israel is now waging a war of retribution against Palestinians, in Gaza and beyond.

“Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” Leo Tolstoy wrote in Anna Karenina. Ethnic conflicts each have their own unique histories, unique emotional resonances, unique forms of repression and terror, unique relationships to empire, and unique ways that international law fails to fit the situation. Syldavians and Bordurians will all say that their struggle is the most special case in the entire world.

All that diverse misery ends up revealing some common patterns. There are infinite ways for one people to brutalize another. Those methods always have the same goal: securing mastery of the land by crushing other people’s ability to resist. And when both sides are forced to accept a ceasefire, the political questions are always the same. The divided people of Cyprus debate whether they need a “one-state” or “two-state solution,” and whether refugees have the “right of return,” just like Israelis and Palestinians do.1

If anything is different about Israel and Palestine, it is the amount of outside attention. Billions of people around the world have lined up behind their chosen proxy. Jerusalem might have the greatest ratio of foreign journalists to locals in the world. U.S. leaders are ready to back Israel to the point of apocalyptic war or national suicide, and Iranian leaders feel the same way about Palestine.

The Holy Land is, well, holy. And it is laden with secular meanings as well. The West, given its recent history, believes it has a moral duty to safeguard the Jewish people. The Global South and particularly the Muslim world see the Palestinian people as the last nation living under colonial occupation. The conflict hits every emotional button in the world at once,2 and gives some outsiders an acceptable outlet for anti-Jewish or anti-Muslim hatred.

The people living in the Holy Land, however, are just people. Israelis got a state out of the 1948 war. Palestinians did not. Israel thinks like a typical conquering state that cannot provide absolute security, and Palestinians think exactly as conquered-but-defiant people would. For all the appeals to ancient history, both peoples are driven by recent traumas. We can’t let the other side win, everyone says, because you see what they did to us in 1948.

There’s nothing wrong with using metaphors to understand this conflict. And it’s possible to debate whether certain analogies do or don’t help. (None will ever fit 100 percent.) But appealing to the complexity of the conflict — making it sound impossible to understand or judge from the outside — is just a way to shut down the conversation. It is the last refuge of people who do not want outsiders to see what they are doing.

A journalist writing about the war or a policymaker working on peace negotiations needs to know all the details. They have to understand the difference between the Green Line and the Separation Barrier, between Jerusalemites and West Bank Palestinians, between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi Jews. But they should also be able to explain themselves to people who don’t know all this history. Human beings are not rocket science.

The West takes opposite positions on the two conflicts, by the way. The United States and Europe support one unified state in Cyprus, with refugees having a full right of return to their old properties. But in the Holy Land, the West preaches that what’s done is done, and that Palestinians should resolve their claims within a separate Palestinian state.

Friedman, Linfield, and Montefiore all make a version of this point — that Israel and Palestine get more attention because they touch on Western cultural faultlines — in the process of arguing that leftists are too obsessively hostile to Jews and Israel.

Calling it an ethnic conflict also muddies the water. It is no more an ethnic conflict than when the local traders get up in arms against paying protection money to the Mafia which happens to be made up solely of Italian goodfellas.