Muslim-American conservatives and the Palestinian question

The rise of Muslim Republicans is going to do some weird things to the politics of Israel and Palestine in America.

Last week, I wrote that Arab-Americans are following the path of recent Italian-American history. Once stereotyped as dangerous foreigners with a sinister culture, they are now being integrated into American society. As part of that process, Islam is starting to be treated like any other religion in North America, for good or for ill.

The past few days of headlines have reinforced the trend. Right-wing media that might have been demonizing Islam a few years ago are busy celebrating their newfound allies. Muslim-American cleric Yasir Qadhi has been leading a public charge against “LGBT-centric values” and the “progressive left.” Muslim conservatives have joined forces with Christian conservatives to protest against LGBT pride and sex education in Maryland and Canada, to the shock of many liberals.

Islamophobic politics in America were always tied to the U.S. wars in the Middle East. Now their importance is fading. It’s become “safe” for Muslim conservatives to side with the Republican Party, and “safe” for Republicans to praise Muslim religious conservatives. The American public, burned out by the War on Terror, pays little attention to Middle Eastern conflicts.

Well, except for one: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Americans have felt strongly about the Holy Land since before the War on Terror, and will likely long after. The Democratic and Republican parties both include staunch pro-Israel constituencies. On the other hand, Palestine is one of the few causes that unites Muslim-Americans (and many Christian Arab-Americans) across ethnic groups, social classes, and levels of religiousness.

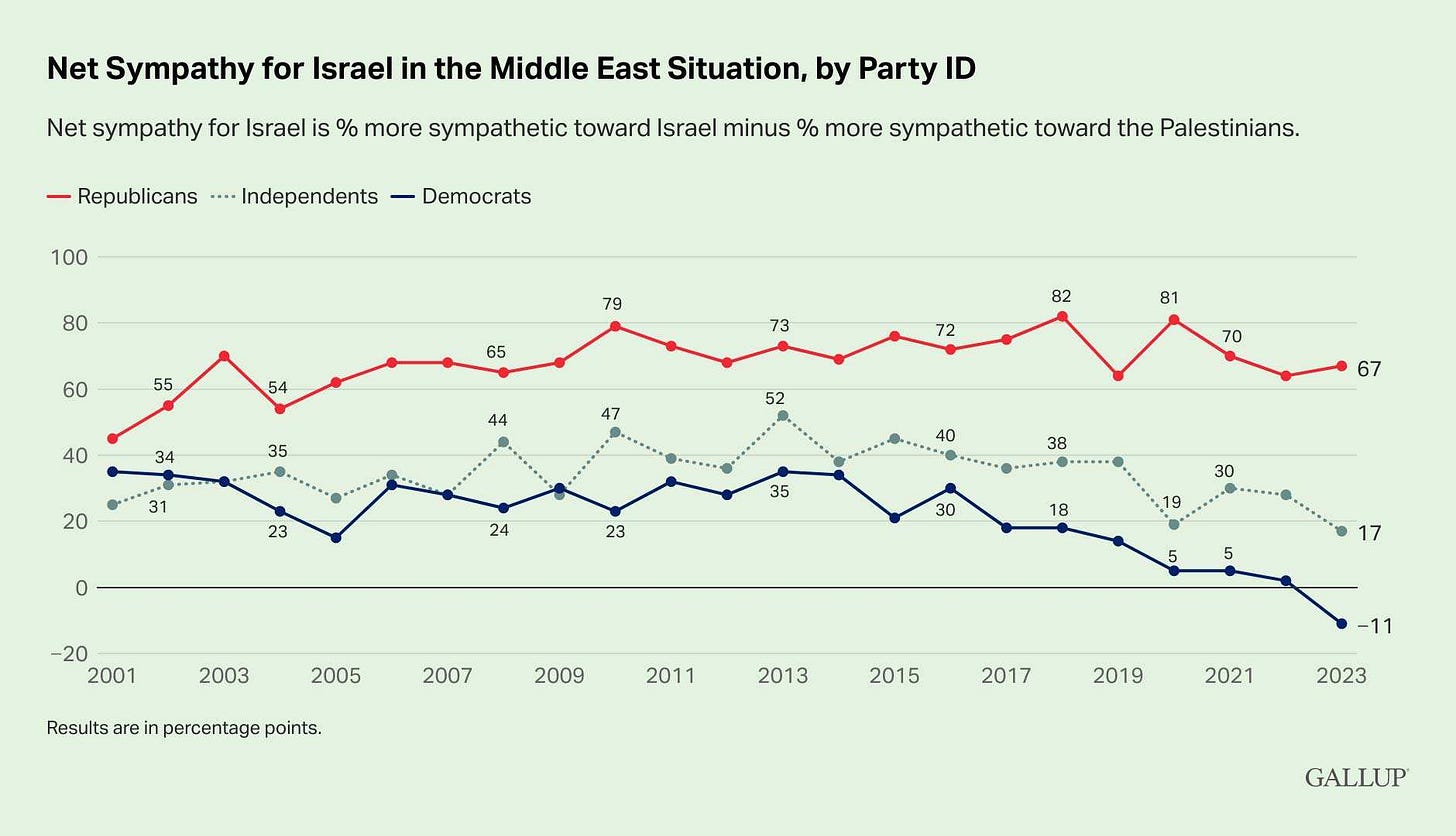

The U.S. political scene is warming up to pro-Palestine positions, but not symmetrically. Polls show that Democratic voters sympathize with Palestinians more than they sympathize with Israelis; among the most famous young Democratic politicians are Palestinian-American congresswoman Rashida Tlaib and outspokenly pro-Palestine congresswoman Ilhan Omar. The Republican Party, meanwhile, has remained pro-Israel on both a popular and elite level.

As the Arab and Muslim communities become more Republican, and the Republican Party becomes more Arab and Muslim, the Palestinian issue will be a point of tension. (Thanks to Connor Mulhern for bringing up this point on Twitter.) A few different things can happen to the politics of Israel and Palestine on the American right; perhaps all of them will happen to some degree.

Here are a few rough possibilities:

The Dr. Oz route: Arab and Muslim Republicans act performatively pro-Israel.

Turkish-American celebrity doctor Mehmet Oz is the most high-profile Muslim in Republican politics today. Before running for office, Oz visited Israeli settlements in the Palestinian territories and was filmed dancing with settlers. During his Senate candidacy, he put out a statement that checked every box on the Israeli nationalist wish list.

This path has some appealing perks. Just as every missionary loves to show off his converts, the pro-Israel movement loves nothing more than someone with an Arabic-sounding name who has “seen the light.” An Arab or Muslim candidate can gain a lot of support from pro-Israel backers — perhaps more than a non-Arab non-Muslim candidate would — by taking public pro-Israel stances.

But the bar for entry is also higher. Even a Muslim like Oz, whose roots are in a non-Arab country friendly to Israel, had to take some pretty hardline positions to prove his pro-Israel credentials. And you can only turn coat once, so to say. Someone who makes “Arab for Israel” or “Muslim for Israel” part of their professional identity is stuck with that label.

On the whole, Arab-Americans will not stop watching news about the siege of Gaza, and Muslim-Americans will not stop caring about the Aqsa Mosque, just because one of their politicians praised Israel at a conference. The Republican Party may end up with “Arab Republicans” and “Muslim Republicans” who don’t represent a real Arab or Muslim constituency.

The loud pro-Israel activism can also be off-putting to people outside the community, even people sympathetic to Israel. Nobody likes a one-trick pony, especially if their one trick is being a defector. Courting pro-Israel activists, like Oz did, is a plausible political strategy. Becoming a full-time pro-Israel activist is the road to irrelevance. There is a fine line between the two.

The Justin Amash route: Everyone politely ignores the Palestinian question.

Justin Amash was a Christian Palestinian congressman who rarely talked about that identity in a political way. (He was elected as a Republican in 2010, joined the Libertarian Party in 2020, and retired the next year.) It’s not that Amash renounced the Palestinian cause; he sometimes voted against pro-Israel bills. But Amash stayed fairly quiet on those votes, and the Republican Party didn’t make him explain himself in public.

Palestine was simply not Amash’s main priority. The same will be the case for many Arab and Muslim politicians on the right, especially non-Palestinian ones. They might get away with mumbling something about the two-state solution and quietly voting against the more egregious pro-Israel laws, while focusing on issues they have more motivation and ability to change.

It can work — as long as no one forces the issue from the outside. Amash was in Congress at a time of solid pro-Israel consensus, which ironically made it easier to “get away” with being Palestinian; his vote wouldn’t change anything, so there was no point in questioning him about his stance. As the Palestinian issue becomes more of a live question, pro-Israel activists will want to pressure any perceived fence-sitters to pick a side.

Amash also had it easier because he was a Christian with a generic Anglo name. Some journalists didn’t even notice that he was Palestinian, let alone the son of a refugee who was expelled by Israel at gunpoint. A mosque-goer or even a Christian with a name like Justin’s father, Atallah al-Amash, would face a lot more scrutiny.

The community itself may demand a firmer stance. While Palestine is an abstract cause for non-Arab Muslims, many Arab-Americans have friends and relatives on the ground. Lebanese-American senator James Abourezk became more vocal about Arab issues, at great cost to his career, after visiting his parents’ village under Israeli bombardment. During the May 2021 uprising, Amash made a rare public comment about his family experience; his father’s old hometown of Ramla was in flames again.

The Black Democrats route: Arab and Muslim conservatives stick to the Democratic Party.

Black Americans vote Democratic about 91% of the time, even though the community is significantly less liberal than the overall Democratic Party on social issues. Black social conservatives prefer to stick with the Democrats — and act as the right wing of the party — than to take their chances voting for Republicans.

Arab and Muslim conservatives could play a similar role, if Republican politics turn out to be too hostile. The current national focus on gender allows Arab and Muslim conservatives to make common cause with other conservatives against liberalism. A return to War on Terror politics would put Arab and Muslim conservatives back in the same boat as Arab and Muslim liberals.

The right’s pro-Israel politics have often been a dogwhistle for going after Arabs and Muslims. Or, in some cases, a bullhorn.

But there’s reason to believe that Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism are a passing fad in Republican politics. These prejudices look more like anti-Catholicism and anti-Italian discrimination, which no one cares about anymore, than white-black racism, which is a deep-rooted issue in American society.

Arab- and Muslim-Americans actually tended to vote Republican before the War on Terror, even with the party’s pro-Israel position. Sami al-Arian, a Palestinian-American activist smeared as a terrorist by the Bush administration, had campaigned for George W. Bush just two years before his arrest. A new Arab and Muslim tilt to the Republican Party would be a return to the mean.

The Chilean route: The Republican Party becomes more open to pro-Palestine politics.

Chile is probably the country with the largest Palestinian diaspora outside the Middle East. The politics around Israel and Palestine there do not line up so neatly with the political spectrum. Plenty of wealthy Arab-Chileans back the political right, and in turn, plenty of non-Arab conservatives in Chile take pro-Palestine stances.

The United States seems unlikely to go down that route. Every political issue is becoming polarized. Israel is a key marker of Republican identity, both because of party ideology and because Democrats are trending in the opposite direction. Arab- and Muslim-Americans are not organized, wealthy, or concentrated enough to repeat the Arab-Chilean model.

However, it’s not impossible. Polling shows that support for Israel has dramatically fallen — really dramatically — among the younger generation of Evangelical Christians, the main pro-Israel constituency on the right. Palestinian-American pollster Shibley Telhami speculated that young Evangelicals are more pro-Palestine because they are a more liberal and multiethnic generation.

The opposite could also be happening: young right-wing nationalists turning against Israel. The nationalist wing of the Republican Party portrays Ukraine as a “globalist” cause forced on America by the “neo-con establishment.” Some right-wing nationalists are starting to see Israel in the same light, whether in the edgy racist or anti-war libertarian sides of the movement.

Of course, these changes would take awhile to translate to electoral politics. But so will the emergence of Arab and Muslim Republican leaders. Just as the Republican leadership is hawkish against Russia but is forced to tolerate Russia doves, the party will remain pro-Israel as a whole but may have to accommodate dissenters on the Palestinian issue.

Again, all of these things can happen together.

Some Arab and Muslim Republican activists may brand themselves as converts to the Israeli cause; others may focus on domestic conservatism while keeping their pro-Palestine sentiments to themselves. On the flipside, some Arab and Muslim conservatives may try to advance the community’s interests (including the Palestinian cause) within the Democratic Party, while downplaying the social issues that divide them from liberals.

The more Arabs and Muslims are integrated into American society, the more their voting patterns and communal politics will look like every other American community. Arab and Muslim working class men will vote along the same lines as the rest of the working class; college-educated Arab and Muslim women will vote the along the same lines as other college-educated women; et cetera.

The biggest question is how Republicans respond to the changing landscape. Right now, conservatives are riding high on the feeling that Democrats have alienated their minority base. But these trends are not guaranteed to last forever, or to benefit the Republican Party automatically.

Republicans failed to make headway with minority voters in 2012 through carefully-calculated pandering and flattery. Then they made historic gains with minority voters in 2020 and 2022, when the party simply talked less about immigration and focused more on domestic social issues. Black and immigrant conservatives will not necessarily be swayed by token minority candidates. They will want to know that Republican policies are not just a dogwhistle for kicking minorities.

For awhile, pro-Israel politics and even anti-Palestinian racism were a cost-free Republican strategy. Democrats weren’t going to punish Republicans for being too pro-Israel, and the Republican Party had plenty of bigger issues with Arab and Muslim voters.

Now Republicans actually do face a tradeoff. On one hand, Israel has become a less of a bipartisan consensus and more of a Republican cause. On the other hand, the other issues stopping Republicans from winning Arab and Muslim voters have disappeared. Although the pro-Israel incentive probably outweighs the pro-Palestine one, the equation is no longer one-sided.

Political realignment is not just a matter of communities switching their loyalty wholesale. New lines are drawn as members respond differently to the changing issues. And the parties themselves learn that, every time they win a new base of support, it changes them a little bit too.