“The Sopranos” is about the Arab-American experience

Italian-Americans faced the same kind of prejudice that Middle Eastern immigrants do. America gave them the privilege to forget.

Senator Bob Menendez of New Jersey is under investigation for corruption, again. This time, the FBI is looking into luxurious gifts that Menendez and his wife got from a meat company. It sounds like it could be a scene from The Sopranos, a show about fictional Mafia boss Tony Soprano, who runs his Italian-American gang out of a New Jersey butchery called Satriale’s Pork Store.

Menendez’s alleged benefactor is different from Satriale’s in one very important respect — it’s a halal meatpacker. No pork on that fork! The company, ISEG Halal, was granted an exclusive license to export halal meat to Egypt, even though its Christian Egyptian owner has no experience in Islamic food laws. The FBI wants to know if Menendez had something to do with the deal; Menendez denies any wrongdoing.

The Italian-American and Arab-American diasporas have more in common than the presence of suspicious meat companies. Both immigrant groups were considered to be on the edge of whiteness when they came to America. And both faced discrimination over the turmoil happening in their homelands.

Italian-Americans eventually assimilated into white America. (So did Arab-Americans who immigrated during Ottoman times; this essay is about the Arab-Americans who came more recently.) Today’s Arab-American community is what Italian-Americans used to be; the Italian-American community may be what Arab-Americans will become.

More than anything else, The Sopranos is a show about that process of assimilation. Tony Soprano is a hardass gangster who grew up in the inner city with hardass immigrant values. Now he’s rich, living in the suburbs, raising two culturally white kids, and going to therapy. The joke is that Tony learns to open up about his emotions to a psychotherapist — like any good liberal upper-middle-class white American would — while still ordering murders.

Tony’s circles complain about “anti-Italian discrimination,” another running joke of the show. Tony believes that the FBI is out to get anyone whose “last name ends in a vowel.” Tony’s psychologist, meanwhile, comes from a family that is angry about the Mafia giving Italian-Americans a bad name.

Tony’s goons even claim that Starbucks is stealing Italian culture. It’s amazing these lines were written before “cultural appropriation” became a well-known issue:

How did we miss out on this? Fucking espresso, capuccino. We invented this shit, and all these other cocksuckers are getting rich off of it...It's not just the money, it's a pride thing. All our food: pizza, calzone, buffalo mozarella, olive oil. These fucks had nothing. They ate puzzi [filth] before we gave them the gift of our cuisine.

These lines are played for laughs, because anti-Italian discrimination doesn’t exist anymore. But it used to. Italian immigrants really did face nasty racism, based on stereotypes about Italian criminality. The joke is less that Tony invented anti-Italianism out of thin air, and more that he is stuck a few decades in the past.

One of the largest mass lynchings in America history was against Italian immigrants. In 1891, vigilantes in New Orleans murdered eleven Italian-Americans after a gangster assassinated the local police chief. The New York Times praised the massacre, calling the victims “sneaking and cowardly Sicilians, the descendants of bandits and assassins…men of the Mafia.”

That article introduced “the Mafia” to American English. Funny enough, the name “Mafia” has an Arabic heritage. Sicily had been ruled by North African Arabs in medieval times, and the word مهياص mahyāṣ (big talker) became mafioso in the Sicilian dialect. If a gangster was a mafioso, then his gang was a mafia.

One of the popular anti-Italian slurs was (and still is) “guinea.” As in, the African country of Guinea. As in, Italians are from Africa, which is supposed to be a bad thing.

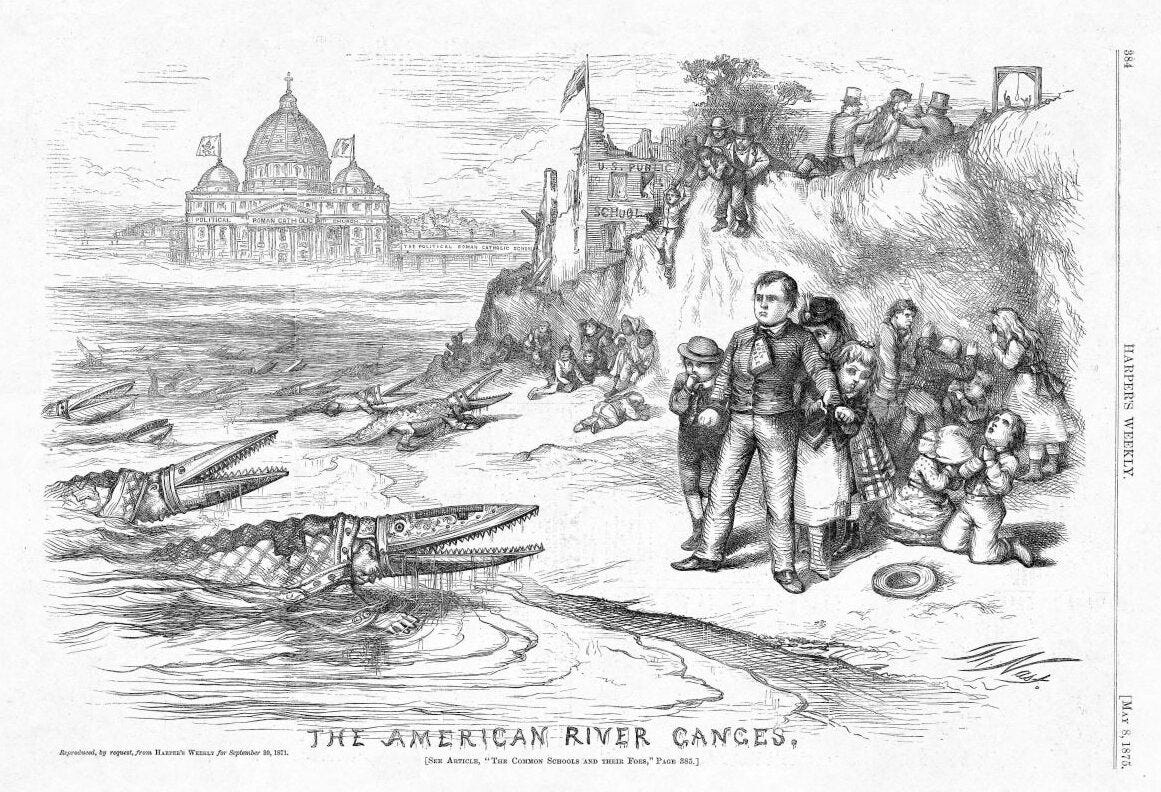

Italians’ Christian religion didn’t help their case, because the Catholic Church was considered just as alien back then as Islam is today. For over a hundred years, U.S. politics were filled with nasty anti-Catholic rhetoric and conspiracy theories about the Pope trying to rule the world. Some of it sounds awfully similar to the Islamophobic conspiracy theories about “creeping Sharia.”

Today’s Islamophobia is largely an outgrowth of national security politics. The United States has been at war in the Muslim world (especially the Arab parts) for four decades and faced Islamist attacks on U.S. soil. Muslim- and Arab-Americans have suffered intense government surveillance and prejudice from the broader society over the perceived terrorist threat.

A century ago, Italians were viewed in a similar light. Like the Arab world, Italy in the 19th century was a patchwork of kingdoms and republics. It took decades of war and revolution to create a unified Italian state. Nationalist leader Giuseppe Garibaldi, by the way, lived in New York for awhile.

Along with pan-Italianism, radical left-wing ideologies were gaining ground in Italy and the diaspora. The Italian community of Paterson, New Jersey became a center of socialist organizing. One of its members, Gaetano Bresci, went back to Italy and assassinated King Umberto. A popular stereotype at the time was the “bomb-throwing Italian anarchist.”

Then there was the case of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two Italian-American anarchists executed in 1920 for a deadly robbery. (Historians still debate whether they were innocent.) Around the same time as the Sacco-Vanzetti trial, the U.S. government launched the Palmer Raids, a mass roundup of four thousand left-wing immigrants, predominantly Italians and Jews.

On September 19, 1920, a horse-drawn carriage exploded on Wall Street in New York, killing 40 people. Still unsolved, the attack was believed to be Italian leftists’ revenge for the Palmer Raids and the Sacco-Vanzetti execution. The Wall Street massacre was the deadliest terrorist incident on American soil up until that point, and is considered the first car bombing in history.

During World War II, the alleged Italian threat shifted from the far left to the far right. The Italian diaspora was seen as a hotbed of Fascist agents. The U.S. government put Italian-American communities under heavy surveillance and even detained Italian citizens in internment camps, albeit on a much smaller scale than Japanese-American internment.

It’s quite similar to how the alleged Arab threat shifted, from left-wing Palestinian militancy to Islamist terrorism.

Just look at the Los Angeles Eight case. Starting in the 1980s, the U.S. government tried to deport eight left-wing Palestinian activists under anticommunist laws. As the case dragged on into the 2000s and the political climate changed, the government then started to prosecute them under laws designed for Islamist terrorism, like the PATRIOT Act.

The obvious contraction between anarchism and Fascism, or between Communism and Islamism, did not matter. What mattered was that Italians and Arabs were foreign, marginalized, and connected to countries where scary violence happens. Of course, none of that applies to today’s Italian-Americans, who are thoroughly assimilated and not associated with any international threat anymore.

Italian-Americans “proved” their loyalty during World War II. More Italians fought for the U.S. military than any other ethnic group — at least, that’s a common Italian-American saying. Even Mafia bosses like Lucky Luciano offered their services to U.S. military intelligence. Some of them later became proxies for the CIA in Cuba. (Funny enough, the top Italian-Cuban drug trafficker was named Santo Trafficante. What’s next, a gun runner named Armando Pistoli?)

The Mafia, the anarchists, and the Fascists all turned out to be a tiny slice of the Italian diaspora. It helps that Italy overthrew Fascism in 1943 and has been a U.S. ally ever since.

A few decades later, the Italian and U.S. governments worked together to crack down on Mafia networks. While the Mafia in Italy fought back with extreme violence and political intrigue, its American branch was basically neutered. New York and New Jersey today are filled with old mafiosi who went soft and transitioned to either legitimate business or very low-level corruption.

The Sopranos is set in that milieu: lucrative, sleazy, sometimes illegal, and a far cry from the glory days of organized crime. It has more to do with shady government contracts and real estate schemes than bank robberies and drug smuggling. Donald Trump, although neither Italian nor part of the Mafia, inhabited the same world before going into politics.

Moving to the suburbs was a major part of assimilation for Italian immigrants. The Roosevelt administration’s New Deal allowed millions of Americans to buy their first home and “graduate” out of the inner city.

Not only did the New Deal uplift urban whites economically, but it also reinforced their social status. Black Americans were denied the New Deal benefits that Italian-, Jewish-, Irish-, and Polish-Americans could enjoy. “White ethnics,” for their funny accents and strange religions, were legally in the same category as white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. They could afford to move on from their early immigration traumas.

Paterson — the industrial city where King Umberto’s assassin lived and where famous scenes from The Sopranos were filmed — is now dominated by Latin American and Middle Eastern immigrants, especially Palestinians. Many of my Jordanian friends know Paterson as the place where their cousins live.

The locals wear gold chains under their sleeveless shirts and talk with the same accent as Tony Soprano, but their last names start with “Abu” or end with “oğlu” more often. Shawarma shops and künefe bakeries have replaced pizzerias. The city’s Main Street has been renamed Palestine Way, complete with 🇺🇸/🇵🇸 flags and keffiyeh-print banners.

The economic and social landscape for Arab-Americans today is very different from the one that “white ethnics” faced a century ago. Still, Arab-Americans are upwardly mobile. The Black Lives Matter moment laid bare the differences between Arab small business owners and their working-class neighbors in the inner cities.

There are also indications that Arabs and Muslims are going the way of Italians and Catholics in the American cultural consciousness. Middle Eastern wars and Islamophobia are becoming irrelevant to U.S. politics remarkably fast. The Republican Party ran a Turkish celebrity doctor named Mehmet Öz for Senate in Pennsylvania last year.

While right-wing Muslim converts like Andrew Tate are no doubt embarrassing to liberal Muslims, they are also a sign that Americans view Islam and Middle Eastern culture as less foreign. Maybe in a few generations, Islamophobia will be like anti-Catholicism, associated with secular liberals rather than anti-immigrant conservatives.

And maybe then, all this War on Terror stuff will be a quirky historical relic. Arab-Americans will have the privilege to — as Tony Soprano likes to say — “fo’get about it.”

Re:the Menendez scandal even if the owners are Christians its not like the owners are the ones butchering the animals, its not as ridiculous as it appeared to be

This is a very naive article that tries to make connections that frankly don't hold up.