Twitter is not real life — even in other countries

There’s a better way to report on foreign social media than just vibes.

The Russian antiwar movement, the Iranian uprising, and now the Chinese anti-lockdown protests. There’s a lot of unrest going on in rival countries, ones that American and European journalists can’t easily get into. Naturally, that has led to a heavily reliance on online reporting.

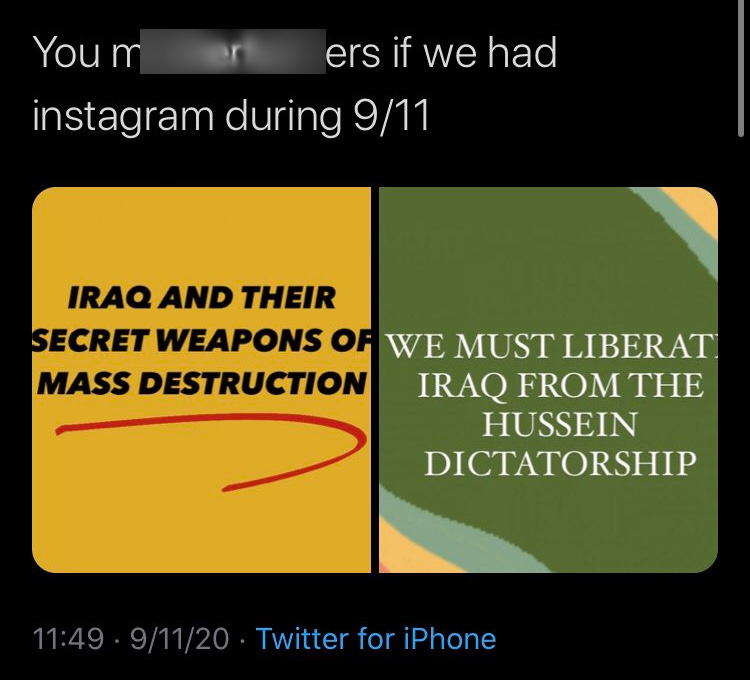

The Internet is critical in these situations, because it allows reporters to safely connect with sources at a distance. But it’s also been used in a more questionable way. Experts have been taking social media as the voice of the “man on the street,” declaring that “Chinese netizens” or “Iranian users” support a certain take, without context on who these commentators are.

Quoting random people as the “vox populi” is an old tradition in Anglo journalism, dating back to the beginning of television. And for at least several decades, U.S. politicians have tried to justify their actions towards other countries by claiming to fulfill the demands of The People in those countries.

The Internet has changed the game.

Social media provides opinion-makers with infinite raw material for constructing an image of a foreign society. Anyone can publish whatever they want online under any identity they choose.

Rather than flying to another country and awkwardly interviewing taxi drivers, or dealing with the messy politics of diaspora organizations, journalists and thinktankers can simply use their favorite website’s search bar to find a local voice who supports their hypothesis.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to foreign policy. Aris Roussinos put it well in his anti-Twitter polemic for UnHerd:

For the online BBC journalist, Twitter is used as a means to circumvent impartiality rules, using often the obscurest of Twitter accounts to voice sentiments they are banned from expressing themselves: when a BBC article tells you that something has “sparked online debate”, prepare for a lecture on the Twitter fixation of the day, in which the quoted account merely ventriloquises the barely-hidden political believes of the journalist sharing it.

I’m certainly guilty of looking to social media for stories on a slow news day.

The more engagement content gets, the greater its apparent credibility. If a post and the reactions to it are constantly showing up on one’s news feed, that certainly feels like a mark of consensus. In fact, some activists have explicitly started to argue that viral posts are the most reliable indicator of what The People are thinking.

Liberal intelligentsia recognize how specious these arguments are coming from their opponents. Infamous coronavirus denier and Donald Trump sycophant Bill Mitchell used to argue that the vibes from “rallies and social media” are more accurate than scientific polling. Elon Musk seems to agree:

Then there’s the common gripe that “Twitter is not real life.” The left wing of the Democratic Party is often accused of inflating its own importance based on its apparent dominance of social media spaces.

Both these examples highlight the problem with treating virality as a synonym for popularity. Leaving aside fake accounts and manipulation — which political operators do engage in — modern social networks put users in echo chambers. Journalists consume social media the same way everyone else does, which means that the algorithm feeds them content they engage with more.

The existence of an echo chamber does prove one thing: that there are enough people having a certain conversation to support a self-contained information ecosystem. However, the number necessary to achieve that is lower than one might think, thanks to Metcalfe’s law.

When it comes to domestic politics, relying on echo chambers has a price. Journalists who fail to describe the reality of their own society will get laughed out of the room.

There are much fewer checks on observers talking about a society that seems alien and closed-off to their audience. In fact, a little bit of wishcasting and playing to biases may be a virtue. To borrow a turn of phrase from Karl Marx, political journalists merely interpret the world, while foreign policy thinktankers are paid to change it.

Language barriers add another layer of distortion. Translating debates in another language takes effort. Selecting what content to translate is always an art. The content that is available in English comes from users who are trying to reach an international audience, and who had the educational background to learn a foreign language.

For better or for worse, the Internet is where everyone goes to have public conversations nowadays. That’s why powerful elites spend so much money trying to censor or co-opt it. Twitter pulled those elites down “onto a level playing field with the crowds to whom they were previously accustomed to simply dictating,” as Murtaza Hussain argued in his delightful “ode to the bird.”

These changes are important to cover in themselves. The medium is the message, as they say, and the new ways people interact with each other online are as much a story as the content itself. Tech publications like Rest of World do an excellent job treating it as such.

Coverage of social media just has to be grounded in an understanding of the human beings behind the screen. Anonymous or not, there should be a sense of what position commentators represent, which parts of society they draw a following from, and whether they are close to any levers of power.

It was probably easier in the old-style “blogosphere.” Commentators had to earn their following by cultivating a unique personality, even if their identity was hidden behind a pseudonym. It felt more like a conversation between individual people than an undifferentiated mass of shouting.

Truly anonymous viral content — or “chain letters,” as they were called back then — was considered the realm of conspiracy theorists, pranksters, and scammers.

Now it’s the default way to consume news.