The death and birth of the Iranian opposition

“Maybe we needed to let the diaspora celebrity ‘activists’ run their course so that everyone can get it out of their system so we can move on to serious change.”

The media coverage an event gets doesn’t necessarily correspond to its importance. During the last couple weeks of Iranian politics, the most well-covered events in English media have been the least important. And vice versa.

Exiled crown prince Reza Pahlavi was met with a gaggle of journalists during his trip to Israel, and a recent Politico article on online opposition infighting has created serious buzz in think-tank circles.

Meanwhile, the breakup of the “Georgetown charter” and backlash to comments by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei have only gotten coverage in specialty Iranian-focused press. And a significant meeting of dissident figures inside the country got just one brief summary and one in-depth article in English-language media.

The paranoid, conspiracy-theory mindset that many exiled opposition figures had promoted is finally catching up to them, poisoning both their internal cohesion and their credibility with the outsiders whose support they were banking on.

However, the conditions in Iran that led to last year’s uprising have not gotten better. The Islamic Republic’s leadership, convinced that it has finally defeated the opposition, is instead doubling down. A natural coalition is forming between longtime dissidents and former regime insiders to push for change inside the country.

As one Iranian-Canadian friend said to me: “Honestly maybe we needed to let the diaspora celebrity ‘activists’ run their course so that everyone can get it out of their system so we can move on to serious change.”

It’s almost cliche at this point to say that the late 2022 uprising was the most serious challenge to the Islamic Republic yet. But it’s a true cliche. Almost all of Iran’s internal tensions and contradictions came together at once. And because the Iranian leadership had shed all pretense of democracy or reform over the previous couple years, dissent had to be all-or-nothing.

International media presented different exiles as voice of the Iranian people and leader of the uprising, as it tends to do during upheaval abroad. The Georgetown charter, announced in early 2023, was supposed to bring them all together. It included Kurdish guerrilla leader Abdullah Mohtadi, human rights lawyer Shirin Ebadi, activist Hamed Esmaeilion, journalist Masih Alinejad, movie actresses Nazanin Boniadi and Golshifteh Farahani, soccer star Ali Karimi, and crown prince Reza Pahlavi.

Esmaeilion is unique among all of those figures for being a total normie. He’s just a dentist. His political journey began when his wife and daughter died on flight PS752, a passenger jet shot down by Iranian air defenses during the January 2020 crisis. Esmaeilion ended up leading the Canadian association of PS752 victims.

By nature of his involvement, Esmaeilion is both the most sympathetic figure in the diaspora opposition, and the one most plugged into today’s Iranian society. (After all, his family was killed for maintaining a connection to the homeland.) But that hasn’t protected him from attacks by the monarchists, who have been trying to muscle out the other members of the Georgetown charter in order to elevate Pahlavi as the sole opposition leader.

Esmaeilion had enough last week. In a long Twitter post on Friday, he announced that he was leaving the Georgetown charter. The coalition was supposed to represent the “diverse and colorful views of Iranian society,” he wrote, but “outside pressure groups tried to impose their positions through undemocratic methods.” Therefore, Esmaeilion was going to focus on the PS752 victims’ legal cases and an Internet freedom project.

“I wish success to the friends of the [Georgetown charter] and I hope that one day we will all live in democracy, freedom, and justice in the shadow of the victory of the women's revolution,” he concluded. “I hope I will see the punishment of the murderers of Iran's children with my own eyes.”

In a TV interview soon after, Esmaeilion specifically pointed the finger at Pahlavi, who had allegedly been trying to stack the Georgetown coalition with his loyalists.

Facing similar pressure, Boniadi deleted her Twitter presence. Alinejad posted a sycophantic pro-Pahlavi and pro-Israel statement after monarchists accused her of antisemitism. Other figures have quietly stopped appearing in Georgetown charter events or materials.

Meanwhile, Politico Magazine published an article about the “threats and harassment” that pro-diplomacy Iranian-Americans have faced from more hardline pro-opposition peers. Although well-written and compassionate towards both sides, the article didn’t really add anything new to the debate. If anything, it focused too much on the problem of incivility, and not enough on the conspiracy theories driving the vitriol.

Still, the article should have been a wake-up call to diaspora activists. Mainstream American media, an important source of exposure and clout in these circles, was starting to take note of the uglier sides of their behavior. And the U.S. foreign policy establishment that these activists hoped to influence was starting to see them as a nuisance. The article quoted think-tankers who believed that diaspora infighting was making it harder for “Iran hands” to “openly discuss and figure out a new policy for the country.”

But enough of the diaspora. What’s happening inside Iran?

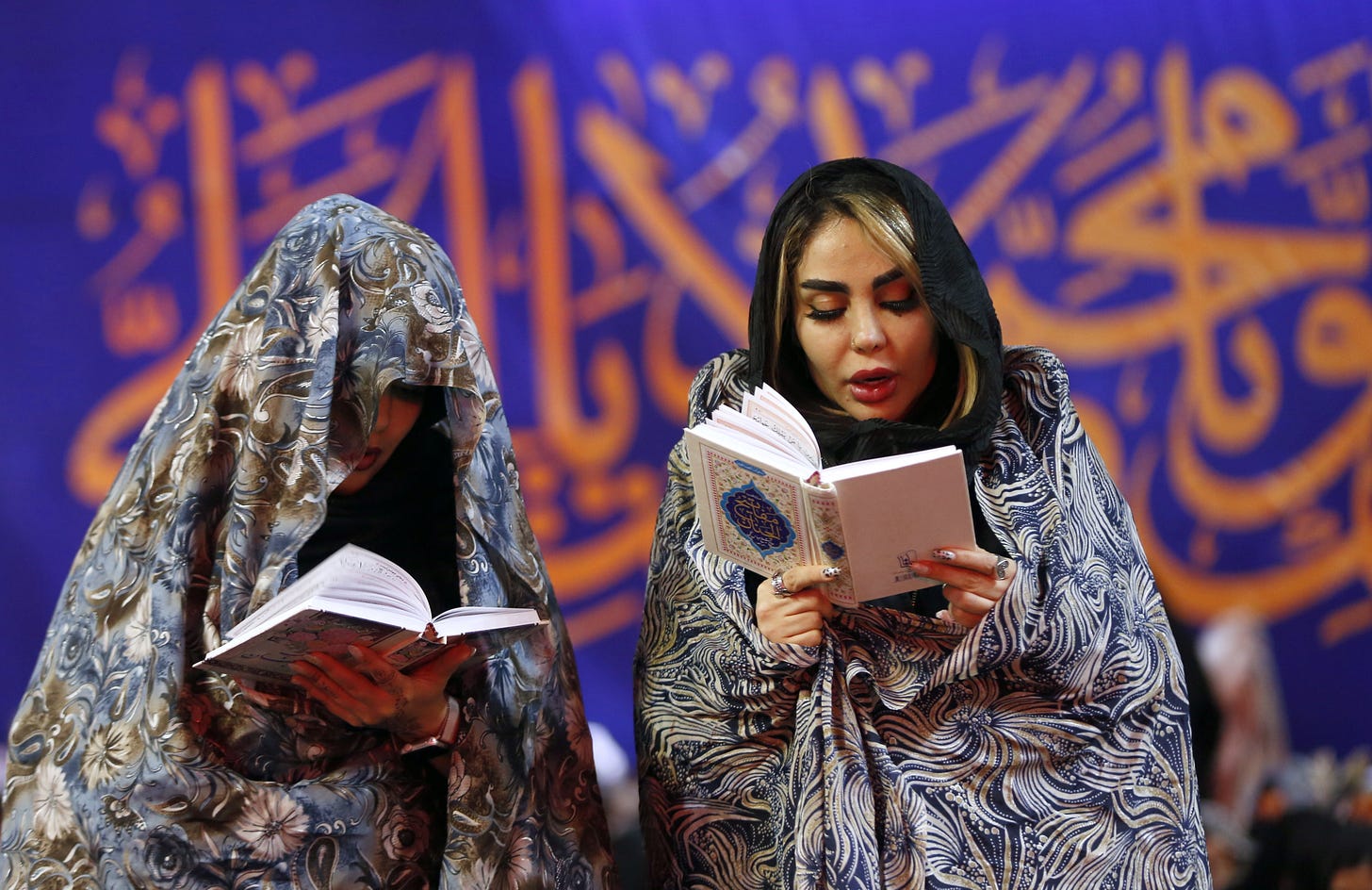

At a meeting hosted by Khamenei for the Ramadan holidays, a student told the Supreme Leader that “we should have held a referendum on various issues from day one” in order to prevent popular discontent. Khamenei answered with a statement worthy of a cartoon villain: “So are all the people who must participate in a referendum able to analyze the issues? What kind of talk is that?”

The comments provoked a reaction even from within the system. The Islamic Association of University Instructors, led by former member of parliament Mahmud Sadeqi, asked Khamenei to “correct his view on the people’s analytical powers and awareness,” and implied that the Islamic Republic is “resisting” a referendum because it knows the results will be unfavorable.

Former president Hassan Rouhani and top Sunni cleric Abdulhamid Ismailzahi have also called for a referendum in recent months.

Khamenei’s contemptful attitude aside, the comments contradict his own positions. The Supreme Leader calls for a referendum as the solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The Islamic Republic still cites a 1979 referendum as the source of its own legitimacy. (The new government passed with 98.2% of the vote after left-wing parties boycotted the election.) In theory, the Islamic Republic’s constitution allows for further referenda on important issues.

Now the Supreme Leader is feeling high on victory. He has successfully rolled back the Reformist wave of the 2010s, reduced Iran’s democratic institutions to nothing, turned himself into a truly absolute ruler, and survived the unrest that followed. The streets have remained relatively quiet, even as the weather gets warmer and Iranian authorities resume enforcing the hijab laws that sparked the 2022 uprising.

But Khamenei’s victory contains the seeds of his defeat. As writer Ali Terrenoire wrote last week, the Supreme Leader has amassed this power not only by defeating the Islamic Republic’s enemies, but also by purging some of its loyal followers:

starting with the liberal nationalists and Communists in the early years of the revolution, to the nationalist-religious (melli-mazhabi) parties, to liberal reformists, Rafsanjani-aligned moderates, the more nationalist and egalitarian groups within the pro-regime Principalist camp (including ex-President and persona non grata Mahmoud Ahmadinejad), and even barred elite moderate conservatives like Ali Larijani from running for President.

There are a lot of post-1979 elites in Iran who would like to bring down Khamenei’s clique, including some very competent, popular, and well-connected officials. In a world where Khamenei had been willing to accept limits on his power, most would have been willing to work within the system; now these former insiders are well-poised to ally with outsiders in a revolution.

Terrenoire believes that the United States does not want such a revolution to happen. A new Iranian government “would have some freedom of choice in its policies” while “inheriting the material legacy of the Islamic Republic that includes an industrial base, a large and well-defined domestic market, advanced military technology, and institutionalized anti-imperialist structures,” he writes.

Iran’s opponents would rather see the Islamic Republic continue to slowly collapse, Terrenoire argues, sapping the country’s economic, social, and environmental base. The foreign-based opposition is useful precisely because it is incompetent. Instead of engaging with either reformists or an independent revolutionary movement, the United States can let diaspora activists stir up instability without any prospect of taking power.

I would go even further, and argue that the United States has actively worked to prevent real change from within the country, as I wrote for UnHerd last year. The most intense U.S. pressure on Iran came after a Reformist government took power. Unprecedented terrorism sanctions also put a target on the backs of the Iranian officer corps, making it clear that overthrowing Khamenei would not save them.

Not only was reform within the system unacceptable to Washington; a revolution by members of the system was also beyond the pale. Only the total and violent destruction of Iranian state structures would be accepted. Or perhaps a slow-motion civil war that pits Iranians against each other on basic questions of identity.

The latter suits Khamenei just fine. He seems willing to bet that patriotic Iranian normies would rather grumble under an unhappy status quo than let someone burn down the social order.

But Tehran and Washington cannot outrun history forever. No amount of Khamenei’s scheming or U.S. pressure can override the massive structural factors pressing on the Islamic Republic.

A couple months ago, former official and jailed presidential candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi called for a referendum on a new Iranian constitution “for the salvation of Iran.” Unlike Rouhani, who called for a referendum on specific issues, Mousavi said that reform within the current system was “impossible.”

This weekend, several dozen figures inside Iran responded to Mousavi’s call. They held an online conference titled, “For the Salvation of Iran,” to discuss how to accomplish his proposal. The discussion brought together an impressive array of figures from Iran and the diaspora: trade unionists, lawyers, journalists, academics, relatives of killed dissidents, and even political prisoners who sent pre-recorded messages from inside jail.

“Mousavi has influence on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, especially the old-guard, as well as the police and military of the country,” said former political prisoner Ali Afshari, who now lives in America and supports a secular republic. “That can help keep part of these forces neutral or convince them to stand on the side of the people who want to transition from the Islamic Republic to a democracy.”

Faezeh Hashemi Rafsanjani, daughter of former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, also attended. She had been arrested for “inciting riots” early in the 2022 uprising, apparently as part of the government’s attempt to pre-emptively shut up any potential opposition leaders inside the country.

The conference received very little attention in English-language media. But Iranians certainly took notice. Right before the conference began, Iranian authorities arrested attendee Keyvan Samimi.

And they scheme, and God schemes, and God is the best of schemers. (Qur’an 8:30)

Update: added a paragraph on Esmaeilion’s interview as well as actions by other Georgetown charter members. Also added the in-depth article about the Clubhouse meeting.

God has blessed the Islamic Republic of Iran with the most useless opposition found anywhere on God's green earth!