Sensitivity Training for Airmen at the Edge of the World

Thule Air Base is beyond the limits of human civilization, but it still hosts colonizers and the colonized.

Learning the local culture is an important part of life on many U.S. bases. You’d think Thule Air Base is not one of them.

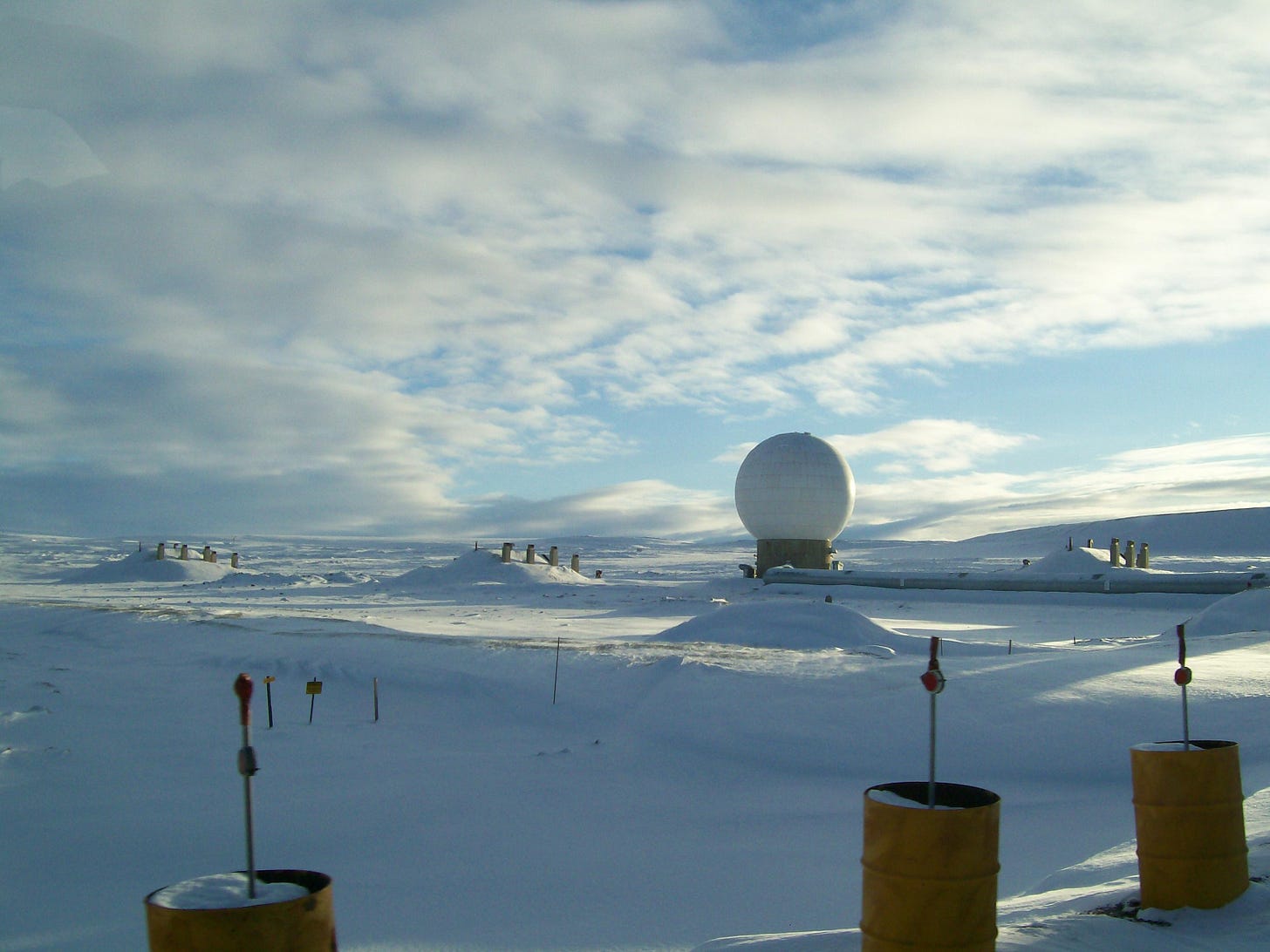

The missile defense base is one of the most remote human settlements in the world. Named after the icy Ultima Thule of Roman mythology, it was built on a former Inuit camp on the northern edge of Greenland. The harbor is frozen nine months out of the year, and the closest village is 65 miles away.

“You can go to the bowling alley, go to the gym, the community center, I guess,” an officer told the military magazine Stars and Stripes. “It’s like a rinse-and-repeat thing. It’s so cold and so dark; where you gonna go?”

But, believe it or not, the airmen and spacemen of Thule get cultural sensitivity briefings. And I have a copy of the documents.

A few years ago, when I was working on a research project about U.S. bases, I saw a press release about “language, regional expertise, and culture (LREC) training” at a U.S. drone base in Niger. I thought it might be worth reporting on the content, so I filed a Freedom of Information Act request for Nigerien LREC materials.

The documents were interesting, although nothing worthy of a breaking news piece. (I may use them for future writing.) It gave me the idea to FOIA other bases’ LREC materials. Why not Thule?

U.S. forces first moved into Greenland after the German invasion of Denmark. Washington wanted to prevent Greenland, a Danish colony, from becoming a Nazi outpost next to North America.

During the Cold War, the U.S. Air Force turned the small weather station in Thule into a base for nuclear bombers positioned close to Soviet airspace. The project took tens of thousands of men and displaced an Inuit village. Today, the U.S. Space Force uses Thule as a surveillance and satellite control station.

The idea of cultural sensitivity training seems ridiculous in a place beyond the edge of human civilization. But the Americans are actually a minority in Thule. The 140 military personnel share the base with around 500 contract workers, who are supposed to be Danish or Greenlandic under the rules of U.S.-Denmark treaties.

U.S. military power exists in a network of bases scattered around the world and connected by airpower, which the historian Daniel Immerwahr calls a “pointillist empire.”

Those bases exist in client states with their own pre-existing hierarchies. They require tens of thousands of civilian contract workers to keep running, especially at the level of amenities the U.S. military offers its troops.

And so the U.S. military ends up subsidizing older social orders and drawing on colonial networks. Base workers in the Persian Gulf, for example, were hired under the same migrant labor system that oil-rich Arab states use, with the same abuses.

Former president Donald Trump, egged on by a cosmetics mogul, tried to buy Greenland directly. The Danish government turned down the offer. It is still a dependency of the Kingdom of Denmark, and U.S. bases still have to hire locals.

Thus the LREC briefing, provided by the defense contractor Vectrus, seems to focus on the intricacies of Danish and Greenlandic culture.

The takeaway throughout is that Danish people are humble, quiet, non-hierarchical, direct in speech, and deadpan in humor. There’s also a slide on Greenlandic culture and the Danish colonization of the region:

Even the icy satellite station in the middle of nowhere still has colonizers and the colonized. It’s a microcosm of the U.S.-led world order.

The whole world is America. America is the whole world. And Thule is its edge.