Rwanda suffered a genocide inside of a war

The pop culture view of genocide in the West hides the way that ethnic conflicts unfold.

There is a debate now about whether the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a genocide against Palestinians by Israel. There are many arguments for or against using that term. (So far, the Israeli military campaign has killed around one percent of the Palestinian population of Gaza, and displaced around 85 percent.) Many pro-Israel journalists, as well as the White House, have attempted to rebut the genocide accusations by pointing out that the Palestinian rebels of Hamas committed war crimes during their October 7 attacks on Israel.

“The ‘genocide’ debate here is activists trying to seize the high ground after Hamas’s hideous acts. Their hope, after an assault of such barbarity, is to label the response ‘genocidal’ and hope that people chase that shiny lure instead of remembering why this war happened at all,” Tom Nichols of The Atlantic recently wrote.

There’s an important point to make here. Genocides often happen in the context of a two-sided war, even wars where the victim’s “side” is guilty of war crimes. Rebel atrocities cannot be an infinite get-out-of-jail-free card for a government accused of genocide. In fact, the Rwandan genocide — the textbook case of a post-World War II genocide — happened at the end of a bitter ethnic war in which both sides had murdered civilians. A defense of the Rwandan genocide would look a lot like Nichols’ statement.

His colleague David Frum, also the Bush administration official who coined the term “Axis of Evil,” mocked people who simultaneously believe “that Hamas is gloriously defeating Israel in Gaza and that Israel is ruthlessly conducting genocide against a defenseless civilian population in Gaza.” That, too, is exactly how the genocide in Rwanda unfolded: the government slaughtered as many civilians as it could before it ran into real resistance and was overthrown.

None of this is to say that the war in Israel and Palestine is equivalent to the Rwandan genocide. Figures like Nichols and Frum, however, are defining genocide so narrowly that even some of the most infamous atrocity crimes in history would not count. Seriously examining the history of Rwanda, meanwhile, can provide some pointers for understanding how ethnic conflicts — including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — unfold.

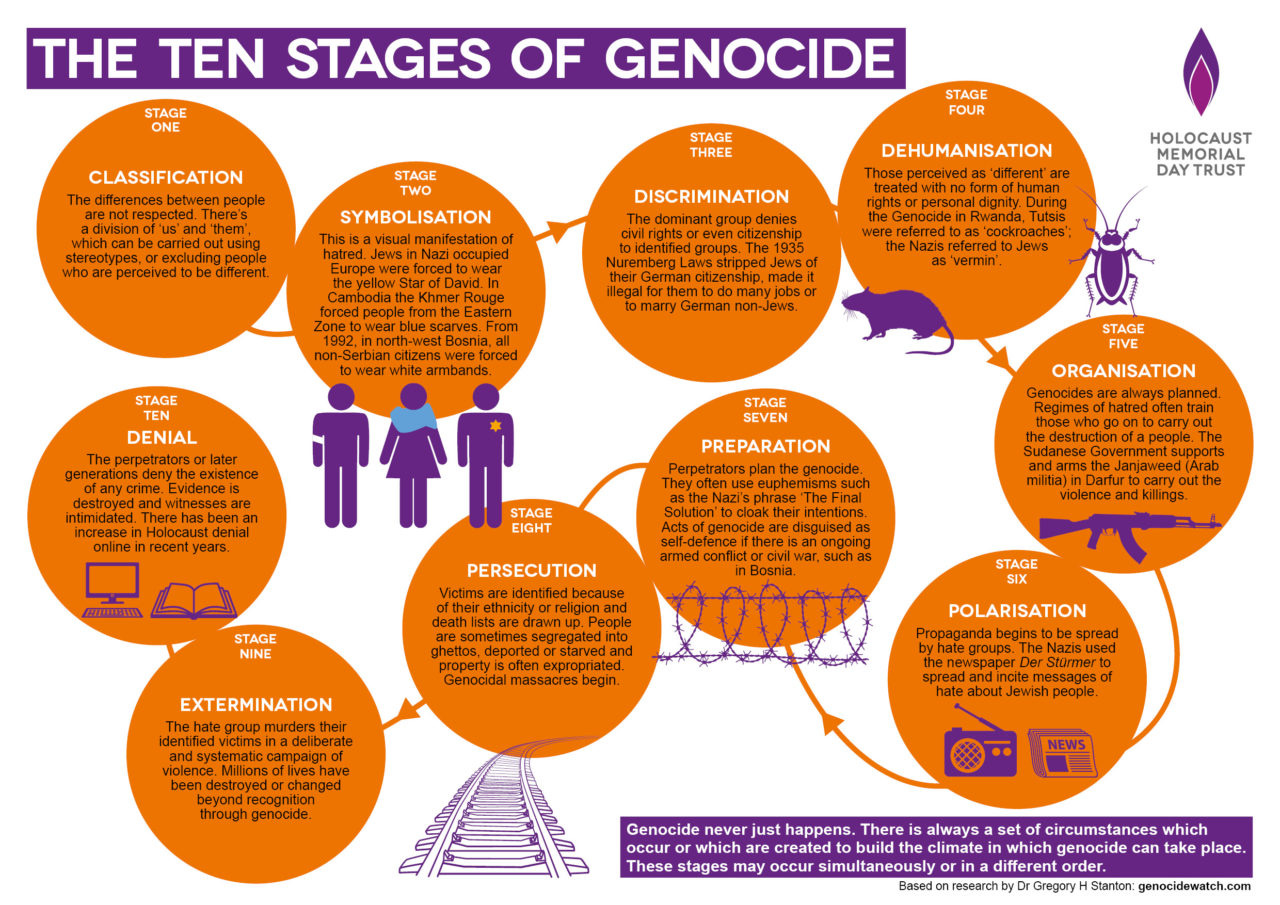

Americans and other Westerners often think of genocide as a mass hysteria event. A society, gripped by intolerant attitudes, begins to discriminate against a minority group. Demagogues begin a deliberate campaign to inflate group differences and inflame the tensions. Once a requisite level of hate has been reached, the genocidaires flip a switch, turning their society into a machine for murdering defenseless minorities.

But real-life genocides do not unfold so neatly. Rwanda had seen a civil war between the Hutu and Tutsi ethnic groups for decades before a Hutu Power regime decided to wage a total extermination campaign against its enemies. The past crimes of Tutsi rulers and future intentions of Tutsi rebels became a justification for Hutu nationalists while they were committing the genocide, and a justification for genocide denial afterwards.

“Hutu” and “Tutsi” originally referred to castes in the medieval Kingdom of Rwanda. Although all Rwandans had a common language and culture, the pastoral warrior elite were called Tutsis and the peasantry were called Hutus. (There was also a third, much smaller caste of hunter-gatherers known as Twa.) During the colonial age, German and later Belgian colonizers kept the Rwandan monarchy in power. The colonial authorities hardened the lines between castes by defining them as separate races.

Near the end of the colonial era, Belgium handed power over to ascendant Hutu nationalists, who forced tens of thousands of Tutsis into exile. An ugly pattern emerged over the next few decades. Tutsi rebels organized in diaspora, demanding their right to return to Rwanda. When those rebels attacked, there were mass Hutu reprisals against Tutsis inside Rwanda, which in turn pushed many of them into exile, where they joined rebel groups.

In neighboring Burundi, where a Tutsi monarchy continued to rule over a Hutu majority, the opposite pattern emerged: Hutu rebellions followed by Tutsi reprisals. These cycles only served to increase Hutu paranoia about what Tutsis would do if they were allowed to return to Rwanda en masse.

Although liberals often blame the Rwandan genocide on Western “inaction,” Western powers were quite active in the region. France helped prop up the Hutu-led regime in Rwanda, while the United States backed neighboring Uganda, whose military was closely tied to Tutsi rebels. By the early 1990s, French leaders actually understood Tutsi rebellions as an Anglo-American power grab against the French sphere of influence. It was one of those rare intra-Western colonial conflicts that survived into the Cold War.

All of these dynamics came to a head in 1990, when the Tutsi-led rebels of the Rwandan Patriotic Front launched an offensive from Uganda into Rwanda. (RPF leader Paul Kagame left his studies at a U.S. military academy to lead the uprising.) While reports of RFP atrocities against Hutu civilians trickled in, the government rounded up thousands of opponents and Hutu mobs attacked any Tutsi civilians they could get their hands on.

Make no mistake: some of the reported rebel war crimes were quite gruesome, including beheadings and sexual slavery. Atrocity stories, both real and imaginary, in turn contributed to vicious pro-government reprisals.

The United Nations eventually brought the two sides to the table, brokering a power-sharing agreement in 1993. While the peace process dragged on, hardline Hutu nationalists began arming themselves for an all-out race war. Then someone assassinated Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana. The hardliners immediately seized power and began to implement a murderous final solution to the Tutsi question.

Soldiers in Kigali, the capital, set up checkpoints and executed anyone marked Tutsi on their ID card. The Interahamwe, a pro-government Hutu militia, began slaughtering Tutsis along with Hutu political opposition. The executions were grisly — most victims were killed with blades — and often involved sexual violence as well. In the infamous Nyange incident, militiamen set fire to a church full of Tutsi refugees, then bulldozed the building on top of the survivors.

Government officials pushed reluctant Hutu civilians to do their “work,” a euphemism for mass killing. Rwandan radio announcers read out hit lists and the location of fleeing targets. Unlike in previous episodes of this ethnic conflict, the Hutu nationalist goal now was to murder the entire Tutsi people, which Hutu leaders cast as an act of self-defense.

“They are going to exterminate, exterminate, exterminate, exterminate,” ranted one Hutu Power politician in an infamous Radio Rwanda broadcast. “They [the Tutsis] are going to exterminate you [the Hutus] until they are the only ones left in this country, so that the power which their fathers kept for four hundred years, they can keep for a thousand years!”

Although the genocide was designed to guarantee majoritarian Hutu rule, it instead rotted and collapsed the foundations of the regime. The army, which had been repurposed for terrorizing innocent people, found itself unable to fight a real war against the RPF — a familiar story. France considered trying to “break the back of the RPF” but ultimately cut its losses, sending troops to safeguard both Hutu and Tutsi refugees. RPF forces overthrew the government in a matter of months, ending the genocide.

By the time the mass murder campaign was over, the genocidaires had killed between 500,000 and 1 million people, including two thirds of the Rwandan Tutsi population. The RPF reportedly massacred several thousand Hutu civilians after taking power. The existence of a two-sided ethnic conflict did not preclude a genocide from taking place; the genocide did not prevent the victims from becoming victors and inflicting violence back.

The deadliest aftershocks were yet to come. The violence in Rwanda spilled over into Zaïre (now called the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and brought down the crumbling regime of Mobutu Sese Seko. The three decades of civil war that followed have killed several million people, with heavy involvement from both the RPF-led government of Rwanda and the Hutu Power remnants in exile.

Western pop culture tends to take some very vague lessons from the Rwandan genocide. “Hate is bad. The world shouldn’t sit by and watch evil.” Often these simple stories are an exercise in hand-washing: genocide is what happens when the benevolent West lets its wayward children stray too far, rather than a problem the West has a hand in encouraging. Even left-wing narratives, which blame Belgian colonialism for creating the Hutu-Tutsi conflict a century ago, often gloss over the role of modern-day French and U.S. meddling.

A deeper look at the Rwandan genocide provides some specific lessons for the present moment. Genocidaires can always argue, sometimes quite convincingly, that “the other side started it.” What matters is which side has the means and (realistic) intent to wipe out the other. No Tutsi could hope to exterminate the Hutu majority, but the Hutu Power movement saw genocide as a feasible and necessary solution.

Israeli politicians have begun to talk about the physical removal of the Palestinian population in the same terms. They believe that all of Gaza — or perhaps all of Palestine — has an insatiable appetite to “exterminate, exterminate, exterminate” Jews unless crushed. Like that infamous Radio Rwanda broadcast, Israeli minister Bezalel Smotrich recently said that “there are 2 million Nazis in [the West Bank], who hate us exactly as do the Nazis of Hamas-ISIS in Gaza.”

Few today want to dwell on historical crimes by Tutsi actors, lest they be seen as blaming the victim. The RPF-led government has tried to build a pan-Rwandan identity that moves past Hutu-Tutsi divisions. For example, it puts great emphasis on mourning political opponents of the Hutu Power regime and other “moderate Hutus” who died during the genocide. On the other hand, RPF leaders are also authoritarian and vindictive, a strong incentive against airing their dirty laundry.

How to deal with historical memory is ultimately a question for Rwandans themselves. If the outside world is interested in taking lessons, though, it should keep in mind that the Rwanda’s genocidaires were able to cite real grievances when carrying out their grisly work. The point is not to justify, minimize, or relativize the genocide. It is to understand that trauma and atrocity can become a pretext for inflicting the worst possible crime on another people.