"Oppenheimer" made history exciting

Nolan did a good job turning bureaucratic drama and World War II intrigue into a blockbuster story. The history was accurate — with some exceptions.

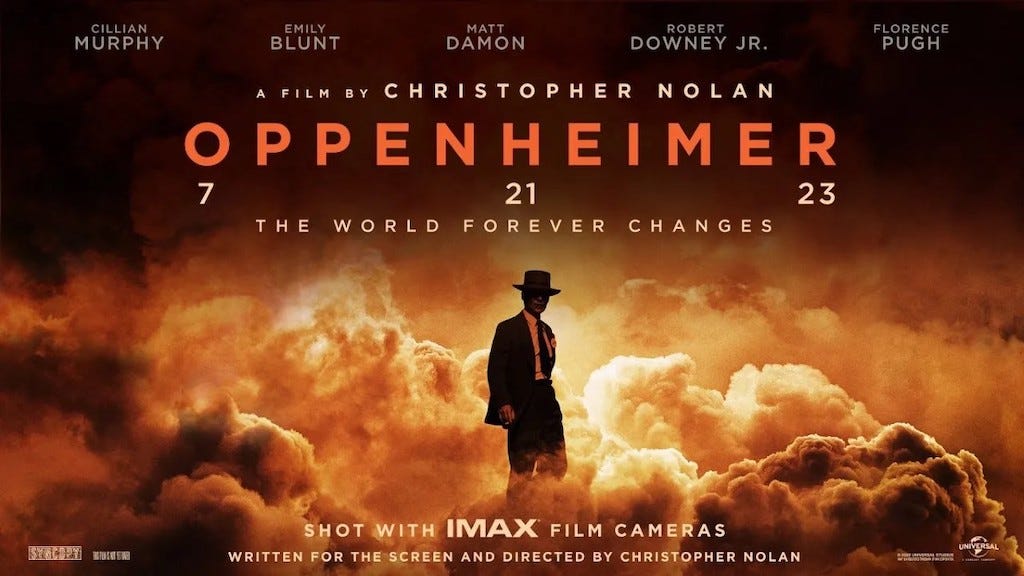

I saw Oppenheimer, the Christopher Nolan movie about World War II nuclear scientist Robert Oppenheimer, this weekend. Unfortunately, Barbie comes out August 31 in the Middle East, so there was no chance for a “Barbieheimer” double feature. The film did quite a good job making history exciting to a mainstream audience, and as someone who’s been reading quite a lot on World War II nuclear history, I’d like to share some of my favorite parts.

This review will have some “spoilers.” (Can you really call it a “spoiler” if the plot is recorded history?) If you’d like to see Oppenheimer without knowing details about the history and the movie’s framing, you can stop here.

The movie’s frame story is an event that happened years after the war: Admiral Lewis Strauss’s Senate hearing. In 1954, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (headed by Strauss) stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance, over his prewar Communist ties. Four years later, when Strauss was nominated to head the Department of Commerce, questions about the Oppenheimer affair derailed Stauss’s own confirmation hearing.

These are boring bureaucratic procedures that most people would never consider Hollywood movie material. But Oppenheimer does a great job capturing the drama, the intrigue, and the spookiness of that era. The movie doesn’t even have combat scenes, despite the wartime subject. Instead, the movie gets the stakes across with military cordons, backroom meetings, FBI spooks rummaging through mail, and Oppenheimer’s own fever dreams about Nazi missiles.

The movie doesn’t just focus on the ethics of building the bomb and Oppenheimer’s guilt over weapons design, but also gets into the more nuanced questions about scientists’ duties and exiles’ loyalties. The American scientific community was very Communist-sympathetic before the war. Oppenheimer’s brother, wife, sister-in-law, and mistress were all card-carrying Communist Party members. Some of the German exiles who worked on the U.S. nuclear program were also leftists.

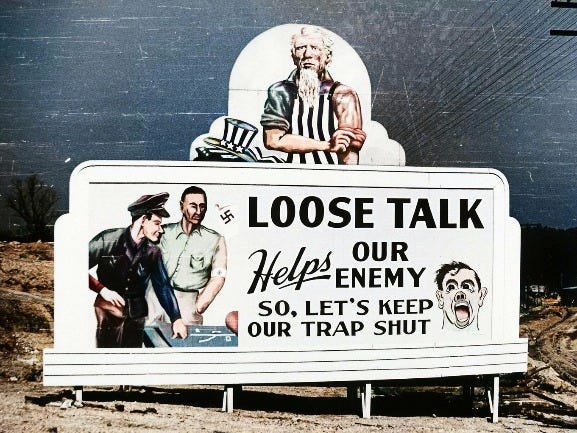

Klaus Fuchs was a literal Communist urban guerrilla in Germany before the war. He fled to Britain after the Nazis’ rise to power, and then joined the U.S. nuclear program, working on the most sensitive parts of the bomb’s implosion design. It turned out that Fuchs was a spy passing information to Soviet intelligence the whole time. Oops!

The movie summed up pretty well the struggle between security and scientific needs — which allowed someone like Fuchs into the program. While General Leslie Groves is obsessed with compartmentalization and information control, Oppenheimer reminds him that “this is a national emergency,” and they need all the scientific expertise they can get. After the war, when Communism was now the main threat, his fast-and-loose attitude with security became a liability.

General Groves testified during the 1954 hearing that he would not grant Oppenheimer a clearance under his interpretation of the current security laws. The movie has him add: “But I wouldn’t clear any of those guys today.” That fictional quote summarizes Groves’ real-life testimony:

You may say what kind of military organization was that. I can tell you I didn't operate a military organization. It was impossible to have one. While I may have dominated the situation in general, I didn't have my own way in a lot of things. So when I say that Dr. Oppenheimer did not always keep the faith with respect to the strict interpretation of the security rules, if I could say that he was no worse than any of my other leading scientists, I think that would be a fair statement.

A friend I watched Oppenheimer with made a pretty keen observation. Werner Heisenberg, head of the German nuclear program, had his own “questionable” associations under Nazi law. Heisenberg looked up to Danish-Jewish physicist Niels Bohr like a father figure, and even met Bohr in occupied Copenhagen. (The play Copenhagen is a really interesting treatment of their relationship.) In an alternative universe, my friend said, there’s a movie about Heisenberg on trial for his association with a foreign Jew.

As an aside, the version of the film I saw replaced the word “Jew” with غريب (stranger, alien, foreign) in the subtitles several times. (For what it’s worth, others who have seen the movie in Arab other theaters tell me that the subtitles did include the word “Jewish.”) I really didn’t like the apparent censorship. Aside from how infantilizing that is to Arab audiences — do they need to be shielded from the existence of Judaism — Oppenheimer’s Jewish background was an important part of the story.

Oppenheimer is an assimilated Jewish-American patriot, putting his scientific prowess at the service of his country. “I know what it means if the Nazis have a bomb,” he says. Albert Einstein plays a sort of foil. He warns Oppenheimer that Einstein’s own country turned against him. Indeed, Oppenheimer says the line about Nazis while defending his own flirtation with left-wing politics.

Ambiguity runs through the movie. Fellow scientist Edward Teller testifies, both in the movie and in real life, that “I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer act in a way which for me was exceedingly hard to understand. I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated.” The film shows that pretty well, from Oppenheimer’s unstable mental state to his complicated moral feelings.

My friend speculated that Oppenheimer’s mysterious demeanor was actually a defense mechanism. When you’re a nuclear scientist in a world war, you really want to keep your political cards close to the chest. After all, the German nuclear scientist Heisenberg survived that way. Historians still debate where Heisenberg’s loyalties lay, and whether he was really working to deliver a bomb to the Nazi regime. Heisenberg lived through the war and was allowed to resume his academic career afterwards.

The spookiest story — and one that really drives home the risks — was the fate of Oppenheimer’s mistress Jean Tatlock. Oppenheimer secretly visited Tatlock, an avowed Communist, in June 1943. (Well, not so secretly, because Oppenheimer was secretly under surveillance by Army counterintelligence agents.) Six months later, Tatlock drowned in her bathtub, leaving behind an unsigned suicide note. It’s been speculated that U.S. military intelligence assassinated Tatlock in order to end the love affair and all the potential security risks associated with it.

The movie is hints at that conspiracy. As Oppenheimer learns of Tatlock’s death, the image in his mind flashes between two versions: Tatlock dunking her head in the tub and gloved hands pushing her down. It was a really subtle scene, and flew over the heads of my friends who hadn’t read the history. Even if the director didn’t want to endorse one version of the story or another, he could have been a bit more clear on what he was suggesting.

Finally, there’s some history the movie gets completely wrong. Oppenheimer sits in on a meeting where military and political leaders debate how to use the bomb. Secretary of State Henry Stimson says that Japan will not surrender without an invasion, and the generals argue that a bomb would kill fewer people than invading. General Groves says that the bomb has to be used twice, once to demonstrate its power and another time to show that the United States has more of them.

As the historian Alex Wellerstein pointed out last week, there are all justifications made up by leaders after the war. During the war, there was no dilemma between dropping the bomb or invading. “The plan was to bomb and to invade, and to have the Soviets invade, and to blockade, and so on,” Wellerstein had written a few years ago. Japan just got lucky that the Emperor decided to surrender after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nor was there a high-level decision to drop two bombs. Bomber crews in the Pacific Ocean were told to use the atomic bombs whenever they were ready. President Harry Truman seemed shocked at how quickly they dropped the second one, and so he ordered no more bombings after that.

The movie stuck to the postwar fairy tales that leaders told about their decision-making process. And in doing so, it missed an opportunity to tell the story well. Oppenheimer is a tragedy about scientists losing control of their work. The real history — where a bureaucracy on autopilot waged nuclear war — drives that point home a lot better than a careful discussion of the pros and cons.

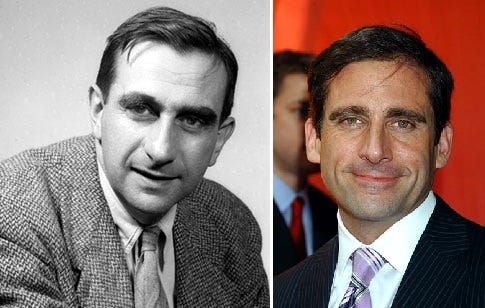

There was one more missed opportunity. Edward Teller, the nuclear scientist who went on to invent the much more powerful hydrogen bomb, is played by Benny Safdie. In real life, Teller looked almost exactly like a young Steve Carell. I am not the first one to notice:

Some might object that Carell is too goofy of an actor to play in such a serious movie. But Teller was a goofy, weird guy, the spitting image of a mad scientist. His hydrogen bomb was one of the few Teller ideas that anyone listened to, because all the rest were insane. The man literally wanted to nuke the moon!

A mad scientist who looks like Steve Carell ranting about nuclear weapons in space, while also inventing an even more destructive version of the most destructive weapons known to man: that’s the dead serious absurdity of the early nuclear age.