Is "intifada" a call for violence?

The word just means "uprising," and the debate is really about whether it's legitimate to encourage Palestinian rebellion.

Students at the University of Michigan chanted for a Palestinian revolution last week, sparking a media furor. Right-wing media, pro-Israel activists, and members of U.S. Congress described their chants as a call for violence or even an anti-Jewish genocide.

The debate centered around the meaning of the word “intifada,” with different sides offering up interpretations. A lot of them are more complicated than they have to be. Intifada just means “uprising,” and Arabic media uses it to describe uprisings all over the world.

Of course, it’s a subjective question whether Americans should be calling for a Palestinian uprising against Israel. But this situation is nothing unique. American activists have cheered on uprisings in lots of different countries, and critics have often called them out-of-touch or dangerous.

The more interesting question is why the word “intifada” is left untranslated, when a simple English equivalent would work. American media likes to use foreign political terms, because they mystify and exoticize conflicts in other countries.

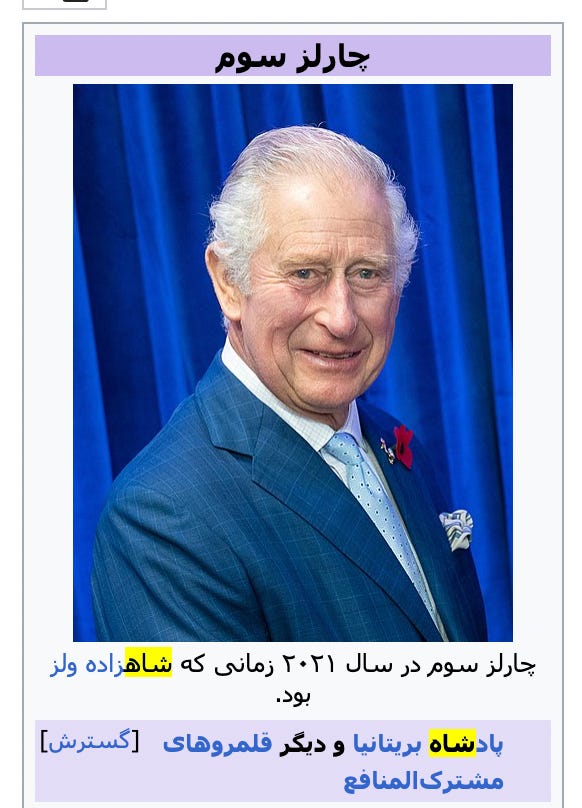

For example, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi is referred to as the last “Shah” of Iran, even though shah just means “king,” and Persian-language media uses that term for every other male monarch in the world.

Or consider the suffix -ista in Spanish and Portugusts.

It has the same etymology as the suffix -ist in English, with the same meaning, too: capitalist, dentist, Buddhist, atheist, activist. Yet news coverage about Latin American politics often leaves it untranslated: sandinista instead of Sandinist, and bolsonarista instead of Bolsonarist.

More sensationalist media also leaves titles like Presidente or Comandante in the original Spanish, even though the English equivalent is quite obvious. Using a foreign word makes these things sound exotic, evoking images of gunmen sipping guava juice and smoking cigars under palm trees.

It’s now become a custom to use -ista to make English-speaking political actors sound edgier. Supporters of Jeremy Corbyn became corbynistas, supporters of Donald Trump become trumpistas, and supporters of Bernie Sanders became sanderistas. At least that last one is fitting; it sounds like sandinista and Sanders did sympathize with the Sandinist revolution.

“Intifada” is one of those words. Dictionaries and news reports often delve into the Classical Arabic root, which has to do with shaking something off. I think that unnecessarily complicates things.

Yes, intifada comes from the word for “shaking,” just like uprising and insurrection come from words for “rising.” In a modern political context, they all mean the same thing.

Don’t believe me? Here’s Arabic-language coverage of the current intifada in Iran, the multiple intifadas in Chilean history, the call for a military intifada in Venezuela, a medieval slave intifada in Mesopotamia, another slave intifada in 19th century Brazil, and the potential intifada of European publics against high gas prices.

In Arabic-language materials, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum refers to the Warsaw Ghetto intifada during World War II.

The word caught on in other languages during the first Palestinian uprising of the late 1980s and early 1990s, then made headlines again during the second Palestinian uprising of the early 2000s. The nature of those two uprisings helps explain why people on both sides leave the term untranslated.

The first uprising was marked by strikes, demonstrations, riots, and other forms of mass political activity. It led to international recognition of Palestinian claims and Israel sitting across the table with the Palestine Liberation Organization. About 1,600 Palestinians were killed, most by Israeli crackdowns and some by Palestinian infighting, along with around two hundred Israelis.

The second uprising was much more violent, especially towards civilians. Palestinian guerrillas used suicide bombings against “soft targets” on an unprecedented scale, as well as random shootings and grenade attacks. Israeli forces besieged entire cities and opened fire on protesters with live ammunition. Around 1,000 Israelis and 3,000 Palestinians were killed.

For Israelis and their supporters, the term “intifada” evokes the second uprising and militant actions of the same nature. Their image of Palestinian nationalism is “hijacked airplanes, homemade rockets, charred wreckage of exploded buses, and, more recently, teenagers wielding scissors and knives,” as the journalist Nathan Thrall describes it in The Only Language They Understand.

The second uprising also lined up with the War on Terror. American audiences were being confronted with a bewildering series of Arabic names in a sinister political context. Giving Palestinian militancy its own foreign word put it in the same category as things like “Al Qaeda” and the “Ba’ath Party.”

Pro-Israel activists may understand the chants of pro-Palestine students as a provocation, invoking the memory of burning vehicles and bloodstained streets that traumatized a generation of Israelis. But there is also a more charitable explanation.

The first uprising was, “for many of the Palestinians old enough to have participated in it, the ‘real’ intifada,” Thrall writes. It was a time when Palestinians felt that they were united and breaking up the status quo to their benefit. That era was not just an uprising but “The Uprising,” a model that defined the term.

The unrest a decade later seemed to deserve the name “Second Intifada,” due to its similarly nationwide scale. Despite various attempts to declare a “Third Intifada,” nothing has really lived up to the phrase, because Palestinian factions have been bitterly divided ever since.

I am not a mind-reader, so I don’t know what meaning the University of Michigan protesters were trying to invoke, the unifying one or the bloodthirsty one. Frankly, the controversy is not really about the term “intifada,” but about whether encouraging Palestinian rebellion is a legitimate political activity.

That same debate can be had about a lot of situations. American activists across the political spectrum have egged on foreigners to risk their lives or shed blood for “freedom,” and American politicians love nothing more than to take photos with other countries’ revolutionaries.

Every side is wildly hypocritical about what they consider patriotic resistance versus evil terrorism.

Debating the etymology of foreign words helps avoid getting to the root of the issue — or applying the principles equally to different countries.