How the search for a downed submarine changed American journalism

The Glomar Explorer, built by the CIA to find the Soviet submarine K-129, gave birth to the "neither confirm nor deny" doctrine.

Submarines. Everyone is talking about them. Last week, a group of wealthy adventurers died when their submarine fell apart attempting to reach the famous Titanic wreckage. The race to find the doomed submariners generated an enormous amount of reporting, commentary, and slightly-distasteful jokes.

A few decades ago, the U.S. government embarked on a similar longshot mission to find a missing submarine. But there was no hope of any survivors. And the government’s attempts to keep the search out of the media reshaped American law forever.

Journalists often talk about the “Glomar exemption” to the Freedom of Information Act. There’s even a verb, “glomarization,” for when the government invokes that exemption. The general public might not know it by that name, but is definitely familiar with the associated phrase: “we neither confirm nor deny.”

“Glomar” refers to the USNS Hughes Glomar (Global Marine) Explorer, a CIA ship that was purpose-built to find a lost Soviet submarine. When journalists caught wind of the expensive and secretive mission, the CIA came up with a new legal doctrine to avoid revealing any details.

In 1968, the Soviet nuclear missile submarine K-129 imploded and sank to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, killing everyone on board. The Soviet Navy could not find the submarine, and wrote it off as a loss. But the U.S. military had detected the sound of implosion, and was able to photograph the wreckage on the seafloor.

Thus began Project Azorian, an $800 million secret operation to pull up the submarine. The U.S. government hoped to inspect a working Soviet nuclear missile and Soviet naval codebooks. In order to keep the mission secret, the CIA worked with the eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes to build an undersea “mining” ship with a three-mile long robotic arm.

In 1974, the crew of the Glomar Explorer set up shop above K-129’s resting place. What they actually managed to recover is a closely-guarded secret, of course. The CIA did eventually acknowledge finding the bodies of six Russian sailors. The Glomar crew had held a haunting secret funeral. The video of the funeral was later released as a goodwill gesture to Russia.

Soviet leadership was impressed with the CIA’s “real technological maneuver,” but annoyed that the agency buried the sailors at sea rather than sending their remains back to the Soviet Union. “If we had recovered your submarine off Murmansk,” a Soviet official told the New York Times, “we would have given back the bodies.”

News of the secret operation had already started to leak out by 1973, when the New York Times’ Seymour Hersh caught wind of the project. CIA director William Colby convinced Hersh to back off while the mission was ongoing. The story broke for real in 1975, when a burglary at Hughes’ company brought international media attention to Project Azorian.

Investigative reporter Harriet Phillippi wanted to know how long the media had held off on reporting Project Azorian, so she filed a freedom-of-information request for the CIA’s contacts with journalists about the Glomar Explorer. Under the Freedom of Information Act, members of the public have the right to request government records. Officials can censor or withhold the documents, but they have to give a reason.

The CIA didn’t even want to acknowledge that it knew about Project Azorian, so the agency told Phillippi that it would “neither confirm nor deny” the existence of such documents. Phillippi took her case to court. Courts ruled in the CIA’s favor: the government can treat the very existence of a file as a classified secret.

The “Glomar response” is one of the most frustrating letters a journalist can get. Lots of agencies use it to avoid handing over documents that are far from sensitive security data. For example, the Internal Revenue Service has refused to confirm or deny the existence of certain tax enforcement cases.

Of course, the Glomar exemption only applies to documents released under the Freedom of Information Act. An agency can’t ban journalists or even other officials from mentioning a topic. That’s led to some pretty absurd situations.

Senator Dianne Feinstein publicly defended the NSA’s surveillance program, but the NSA refused to confirm or deny its existence. Former president Donald Trump wrote on Twitter that he was “ending massive, dangerous, and wasteful payments to Syrian rebels,” but the CIA argued that Trump wasn’t actually publicizing the existence of any payments, and a judge agreed.

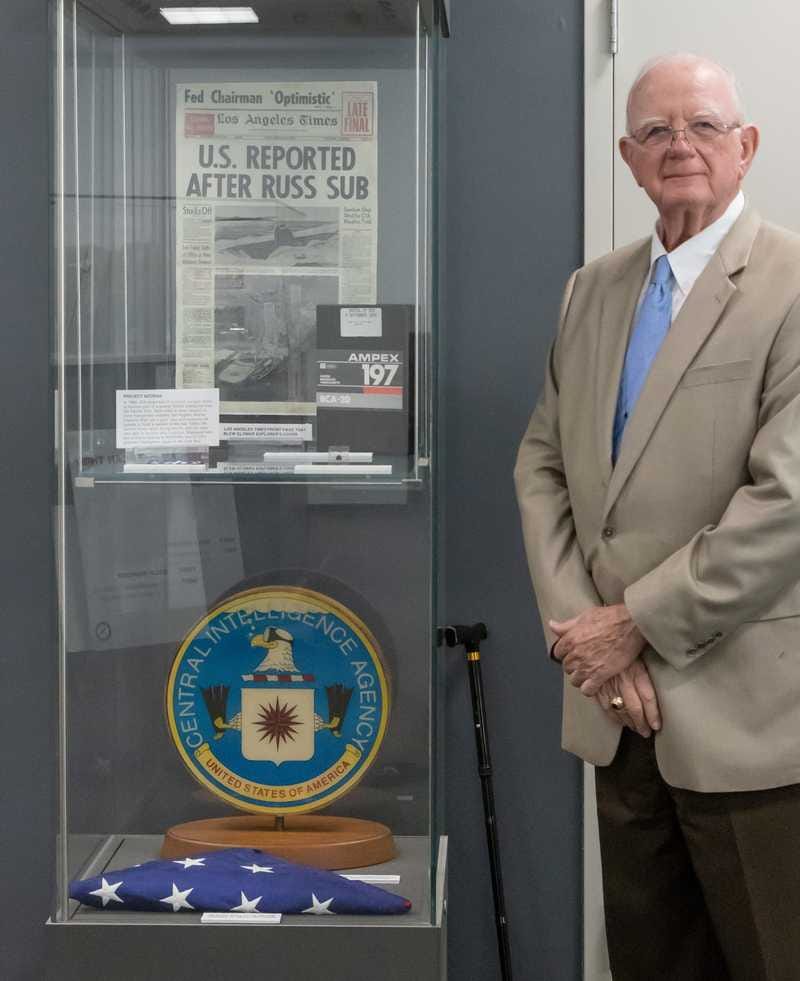

Ironically, the CIA loves to talk about the Glomar Explorer today. Now that the Cold War is over, it’s safe to brag about the technical feat. The agency maintains a physical and virtual museum on Project Azorian — including the history of how the operation was exposed to the press.